Photos by Nile Scott Studios and Maggie Hall

‘

By Shelley A. Sackett

P. Carl, an acclaimed educator, dramaturg, and writer, lived for 49 years as Polly, a woman who believed she had been born into the wrong body. The last 20 years were spent as a lesbian in a queer marriage to Lynette D’Amico, a writer and editor. Lynette had no idea the queer woman who was her wife suffered gender dysphoria, a condition that can — and in Polly’s case, did — lead to depression and anxiety and have a harmful impact on daily life.

So when, at age 50 and against the backdrop of America’s changing LGBTQ+ political and cultural backdrop, Polly decided to undergo gender transition and become Carl, it came as quite a surprise.

In 2020, P. Carl published a memoir, “Becoming A Man,” that detailed his life before, during, and after his transition, sharing details of what it was like to grow up in the Midwest as a girl, become a queer wife and successful career woman, and then transition to life as a man at the height of the Trump era.

A.R.T. Artistic Director Diane Paulus had read an early draft of the book and thought it would translate well as a play. P. Carl agreed. A commission of this new work for the A.R.T. and a several-years-long developmental process resulted in the dramatic version of “Becoming a Man,” in its world premiere production at Loeb Drama Center through March 10.

Act II, a facilitated conversation with the audience about the play and its themes, immediately follows the play. Facilitators are chosen from a roster of local leaders, artists, or medical professionals, and activists who explore the production’s essential question, “When we change, can the people we love come with us?”

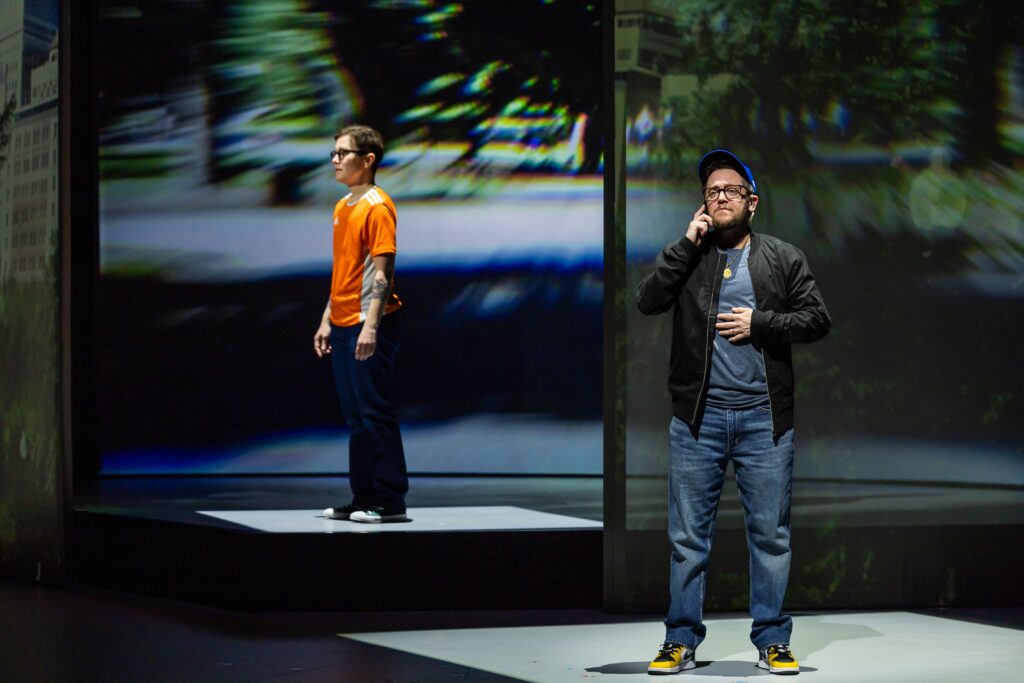

“Becoming a Man” functions largely as a non-linear narrative of P. Carl’s journey and female-to-male transition from Polly Carl to Carl. It opens with a bearded Carl (Petey Gibson) catapulting onto a minimalist stage, declaring that his decision to transition from female to male was the best move of his 50-year-old life.

“The world shifted,” he explains. “I finally learned to swim,” a metaphor that pops up frequently for the euphoric freedom of finally feeling comfortable enough in one’s own skin to risk exposing it to others in very public places.

Carl also admits that now he is a man, he has become a bit of an uber-male. He enjoys men-only spaces, like sports bars, where he yells at the television and refers to his wife as the little woman. He hires a personal trainer and practically swoons in the men’s locker room. He even develops a sneaker fetish.

He also is clueless and blindsided when his lesbian wife Lynette (Elena Hurst) doesn’t react to his transition as the enthusiastic cheerleader he had assumed she would be. Myopic and self-reflective and -involved to a fault, Carl honestly doesn’t get it that Lynette could be traumatized by her female wife becoming a male and by hearing that during the entirety of their marriage, that wife felt like she was living in a body that was a lie.

Lynette, after all, fell in love with Polly and embraced their female queer personal and political status. She liked every aspect of being in a female-female marriage. Suddenly, to remain married to the person she loves, she has to do a 180 and adjust to the new reality that they will now present to the world as any other conventional heterosexual couple.

“What’s my part in your new life?” she asks. “I don’t know who you are. You obliterated my past,” she says, adding for emphasis, “I did not accidentally omit men from my life.”

“Transitioning for me was a breeze,” Carl says blithely. “She’s grieving and I’m celebrating.”

To his great credit and the audience’s edification and enjoyment, Carl presents his personal story in an honest, no-holds-barred way that is deeply touching in the level of trust and introspection it shares.

His pre-transition self, Polly (Stacey Raymond), is her own character, often shadowing Carl and reminding him of who he was as he navigates who he is. The moments when Polly, horrified by Carl’s macho behavior, scolds him are among the play’s best.

Raised in Elkhart, Indiana by an abusive father (Christopher Liam Moore) and loving but passive mother (Susan Rome), Polly is proof that the internal pain and trauma of a childhood spent in a small-minded Midwestern town as a girl feeling like she was a guy who was attracted to girls is as difficult to shed as the external signs of gender assignment.

Polly’s difficult relationship with her family is no less difficult as Carl, and the scenes when both visit their father in his waning years spotlight the point that inside, Carl really is also Polly, with all her assets and all her baggage.

“Becoming a Man” tries to cover a LOT of ground (to varying degrees of success), including friendship, gender, power, sexual identity, and inequality in America. Perhaps the most interesting and poignant topic is how the person who transitions and those with whom they shared relationships deal with all the memories and experiences that happened during pre-transition life.

Ironically, it’s the two women in Carl’s life who remind him that his actions have consequences that extend beyond his body.

“You don’t get to choose what to remember and what to forget,” Polly chides Carl. “I don’t know what to do with our history,” adds Lynette.

Becoming A Man’ — Written by P. Carl. Co-directed by Dianne Paulus and P. Carl. Scenic Design by Emmie Finckel; Costume Design by Qween Jean; Lighting Design by Cha See; Music and Sound Design by Paul James Prendergast; Video Design by Brittany Bland. Presented by the A.R.T. at the Loeb Drama Center, 64 Brattle St., through March 10.

For tickets go to https://americanrepertorytheater.org/