Photos by Jim Sabitus

By Shelley A. Sackett

To Kill a Mockingbird, the 1960 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel written by Harper Lee and dramatized in 1970 by Christopher Sergel, tells the story of events that take place in the small town of Maycomb, Alabama, during the Depression (1932 to 1935). The plot and characters are based on Lee’s observations of her family, neighbors and an actual event that took place in 1936 near her hometown, Monroeville, Alabama.

Lee was 10 years old at the time, the same age as Scout (Jean Louise), her novel’s narrator and thinly veiled stand-in for the author. In the theatrical version, 10-year-old narrator Scout is replaced by her adult self, Jean Louise, adding a layer of nuance.

The play (145 minutes, one intermission) follows the lives and rich imaginations of the Finch children (Scout and her older brother, Jem) and their friend, Dill, who visits his aunt in Maycomb for the summer. Maycomb is a quiet town with deep-seated social hierarchies based on race, class, socioeconomic status, and how long each family has lived there.

Its residents are closely knit and tightly wound. There are strict lines about gender, class, social standing, finances, and most important of all, race, and those who cross those lines do so at their peril.

Atticus Finch, Scout and Jem’s widowed father, is a middle-aged lawyer with a strong sense of right and wrong and a dignified, gentlemanly bearing. He encourages the children to think of Calpurnia, their Black cook and caregiver, as family. He approaches their every question as a teachable moment, and breaks down huge issues into bite-sized morsels they can digest more easily.

Most important of all, he tries to instill in them the ability to feel empathy before criticizing or condemning. “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view […] until you climb into his skin and walk around in it,” he tells Scout and Jem. Everyone is equal in Atticus’s eyes, and the weakest must always be defended against the most powerful.

For the most part, the children busy themselves each summer with convoluted plans to lure their reclusive neighbor, Arthur “Boo” Radley, out of his house. Miss Stephanie, one of the town’s Queen Bee gossips, has filled their heads with tales of Boo as a mysterious and dangerous person who even stabbed his own father with a pair of scissors.

They start to notice small gifts left in the knothole of a tree, and assume they are for them. They also assume they are from Boo, even though they’ve never laid eyes on him.

Soon after, the atmosphere in Maycomb becomes thick with unbridled prejudice and raw hate. Atticus is appointed to defend Tom Robinson, a Black man falsely accused of raping Mayella Ewell, a White woman. Atticus believes every person deserves a fair defense; he doesn’t just talk this talk, he relishes the opportunity to walk the walk, his back straight and his head held high.

The townspeople aren’t as civic-minded, and both Atticus and his children are soon the targets of mob terror tactics.

One of the book’s most poignant scenes (well adapted by Sergel) is when Scout outs a masked man who has come with his posse to menace Atticus as he stands guard all night at the jail where Robinson is being held pending trial.

“Hey, Mr. Cunningham,” she says, recognizing his hat. She asks about his family (she knows they have no money as she earlier witnessed him paying Atticus’s fees with turnips and kindling) and asks him to say “hey” to his son, who is in her class at school.

Shamed and embarrassed, Cunningham calls off his pack dogs and heads home.

Things heat up even more after the trial (among the play’s — and book’s — best scenes) and boil over one night when Scout and Jem are attacked in the woods. Despite disappointment and tragedy, all is eventually resolved, and there is a sense of closure and hopefulness by the play’s end.

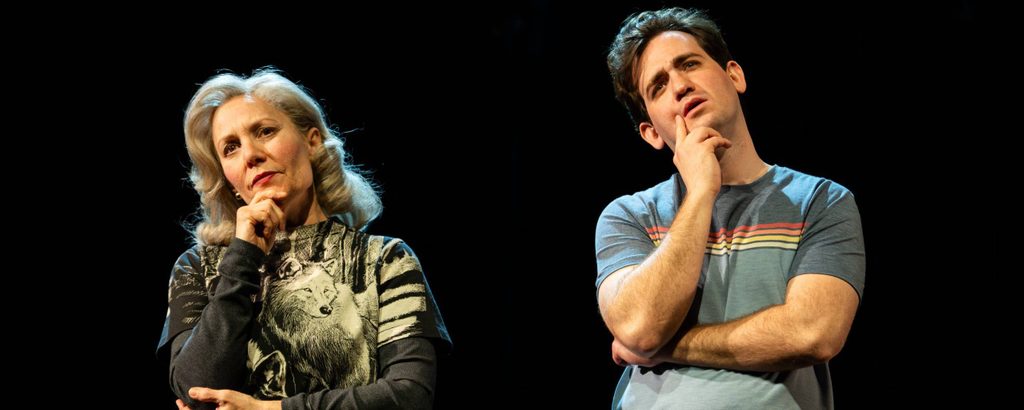

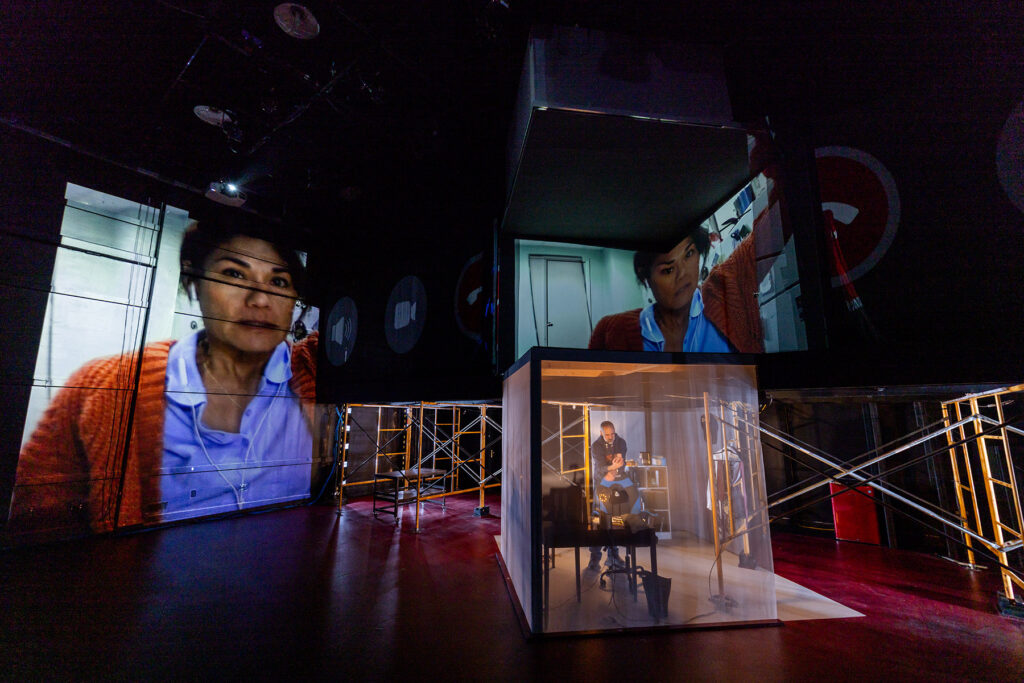

Director Scott Edmiston uses Janie Howland’s simple but elegant set to his best advantage, and the addition of Valerie Thompson’s emotive solo cello is a stroke of brilliance. In a cast of many, Amelia Broome (adult Jean Louise Finch), Carolyn Saxon (Calpurnia), Bryce Mathieu (Tom Robinson), and Barlow Adamson (Atticus) stand out.

As impressive as it was that the three youngsters playing Scout, Jem and Dill learned so many lines, it was sadly impossible to hear and understand their words. Frustrating for the audience; tragic for the actors.

To Kill a Mockingbird, with its themes highlighting racial prejudice, moral courage, and lost innocence, is as relevant today as it was when written. To wit, it is frequently challenged and has been banned or removed from various school districts across the U.S., including in Mississippi, California, and Virginia, often due to its use of the N-word, racial slurs, and uncomfortable themes regarding race. While it is not nationally banned, it consistently appears on the American Library Association’s (ALA) list of most challenged books, frequently ranking in the top ten.

What a shame that the lesson of love and respect at the heart of this work is so feared by those who need to hear (and heed) it most. As Atticus so eloquently explains to his young daughter, “Shoot all the bluejays you want, if you can hit ‘em, but remember it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.” After all, mockingbirds are delicate, vulnerable creatures who never do anything harmful. All they want to do is to pleasure others with their clear, beautiful singing.

‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ — Dramatized by Christopher Sergel. Based on the Book by Harper Lee. Directed by Scott Edmiston. Scenic Design by Janie Howland; Lighting Design by SeifAllah Salotto-Cristobal; Costumes by Rachel Padula-Shufelt; Sound Design by Chris Brousseau; Original Music on Cello by Valerie Thompson. Presented by The Umbrella Stage Company, 40 Stow St., Concord, MA, through March 22.For more information, visit https://theumbrellaarts.org/