“The Winter’s Tale.” Written by William Shakespeare. Directed by Bryn Boice. Scenic Design by James L. Fenton; Costume and Wig Design by Rachel Padula-Shufelt; Lighting Design by Maximo Grano De Oro; Sound Design by David Remedios; Original Music by Mackenzie Adamick. Presented by Commonwealth Shakespeare Company for Free Shakespeare on the Common, Parkman Bandstand, 139 Tremont St., Boston, through August 4.

By Shelley A. Sackett

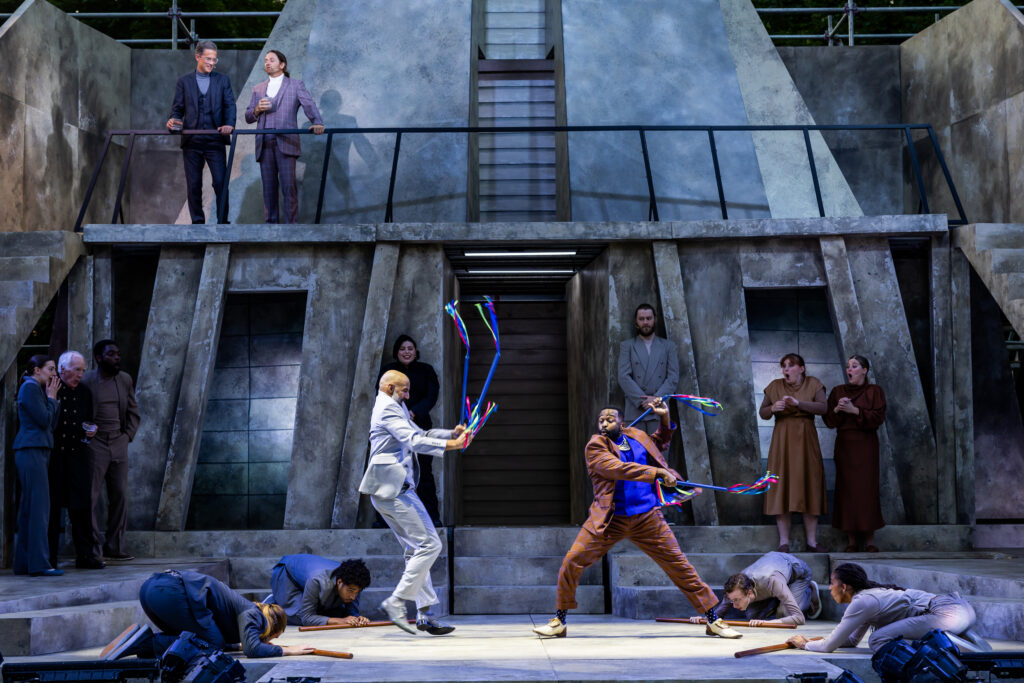

The drizzly chill overhead did nothing to dampen Commonwealth Shakespeare Company’s sizzling (and free!) production of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. From James J. Fenton’s spectacular set to director Bryn Boice’s nuanced yet spunky direction to the exceptional cast, the evening was an example of Boston’s cutting-edge theater scene at its most exciting.

Although the clear-as-bell sound (Sound Design by David Remedios) and colloquial cadence of the actors’ deliveries didn’t require them, two large screens with closed captions were an added bonus, enhancing our ability to really savor Shakespeare’s Elizabethan verse. (There are some truly great and rarely quoted lines in this play.)

The Winter’s Tale was dubbed one of Shakespeare’s four “problem plays” by English critic and scholar Frederick S. Boas because it doesn’t fit neatly into the silos of tragedy or comedy but rather straddles the two. According to Boas, Shakespeare’s problem plays set out to explore specific moral dilemmas and social problems through their central characters. Boas contends that the plays encourage the reader to analyze complex and neglected topics. Instead of providing pat answers and arousing simple joy or pain, the plays confuse, engross, and bewilder.

Boas certainly was spot on as far as The Winter’s Tale is concerned.

The action opens with a full head of steam as a large cast of well-dressed men and women cavort in the castle of Leontes, King of Sicilia (played by the always magnificent Nael Nacer). His pregnant wife Hermione (a radiant Marianna Bassham) and their son are surrounded by loved ones as they entertain King Polixenes (Omar Robinson, fresh from his success in “Toni Stone”), Leontes’ childhood best friend and king of Bohemia.

Polixenes is set to depart for Bohemia after a nine-month visit to Sicilia. When Leontes’ attempts to persuade him to stay longer are unsuccessful, Hermione playfully takes up the challenge. After some innocent and very public mock hanky-panky of hand-holding and cheek-pecking, she accomplishes what Leontes could not. Polixenes will stay one more day.

As the audience witnesses the lightness of Polixenes and Hermione jesting stage right, there are dark clouds gathering stage left, where Leontes is slowly going off the rails. Nacer brings the full force of his physical talent to bear as we swear we see Leontes grow antennae that crackle and hum with every word spoken and gesture exchanged between his wife and best friend.

By the end of the scene, Leontes has gone feral, descending into an all-consuming raging derangement of sexual jealousy. He convinces himself that Hermione has cheated on him with Polixenes and that the baby Hermione carries is the result of the affair.

Leontes plunges into a madness that makes MacBeth and Hamlet look like amateurs. He transforms from a benevolent king to a tyrannical despot, declaring that Hermione will be tried for her crime of adultery, the punishment for which is imprisonment and possibly death. Othello may have his Iago, but Leontes has no need for anyone to egg him on; he is both torturer and the tortured, “in rebellion with himself.”

He entreats Camillo (an engaging Tony Estrella), his cupbearer, to poison Polixenes, but Camillo instead warns Polixenes and flees to Bohemia with him. Not even Paulina (the fabulous scene-stealing Paula Plum), a loyal lady-in-waiting to Hermione and the voice of Leontes’ conscience, can persuade him he is wrong. He can’t see that rather than outraged victim, he is the outrageous culprit.

Hermione gives birth to a girl, Perdita (Clara Hevia), whom Leontes commands Paulina’s husband, Antigonus (Robert Walsh) to abandon in Bohemia. On that dark note, Act I closes as the madness of Leontes’ paranoid jealousy takes its toll, leaving him standing in the smoldering ashes of what once was the heart and hearth of his family and kingdom.

Act II opens in a 180 degree turnabout, the comic antidote to Act I’s tragedies. Both Shakespeare (with his clown and trickster characters) and Boice (with her 21st century spin) have some fun.

Sixteen years have passed. Shakespeare has created a Greek chorus of one in his character Time, gifting her with an explanatory monologue that no one but Plum could deliver with such grandeur and emotion. Boice’s staging is breathtakingly brilliant.

Perdita, who ended up in Bohemia and was found and raised by an old shepherd (the endearing Richard Snee), is throwing a sheep shearing party to end all sheep shearing parties. It is the equivalent of her sweet-16, coming out celebration. Techno music reverberates. Neon abounds (Lighting Design by Maximo Grano De Oro). The guests dress and behave like MTV extras (Costume and Wig Design by Rachel Padula-Shufelt).

Although (like many MTV routines) it goes on a little too long, the scene draws our attention to the stark contrasts between the doom and gloom of Act I’s despotic Leontes’ Sicilia and Act II’s kinder, gentler Bohemian landscape and lordship.

Perdita even has a boyfriend, King Polixenes’ son Florizel (Joshua Olumide). Their relationship is the balm that ultimately heals the rift between their fathers and their kingdoms, a testament to Virgil’s poetic phrase, “Love conquers all.”

Eventually, all ends well enough and Shakespeare manages to reunite friends, foes and family. Leontes repents for his misguided ways, reaping forgiveness and sympathy. As far as he is concerned, he is redeemed and pardoned for his brutal and abusive misuse of power of trust. The death and destruction he caused was collateral damage, water under the bridge. Even Hermione, trapped as a statue, is resigned and forgiving.

Yet, the Bard has left a bitter taste in our mouths.

Boas was right about problem plays. “The Winter’s Tale” certainly explores specific moral dilemmas and social problems through its central characters, leaving us indeed engrossed and bewildered, especially given the discordant nature of the nation as it faces yet another toxic election season.

It is hard to sweep aside the gravity of Leontes’ transgressions and the sleight of hand by which they vanish. He wrecked a world and is then put on a pedestal when he conveniently comes to his senses and rues his own loss. Where is the fairness in that? What moral, social messages are we meant to take away? Where, Mr. Shakespeare, are the eloquent railings against tyranny, toxic masculinity and falsehood? Where are the consequences for immoral and corrupt behavior? And, a few empowering monologues notwithstanding, where have you left your women?

Highly recommended.

For more information, visit commshakes.org/production/winterstale.