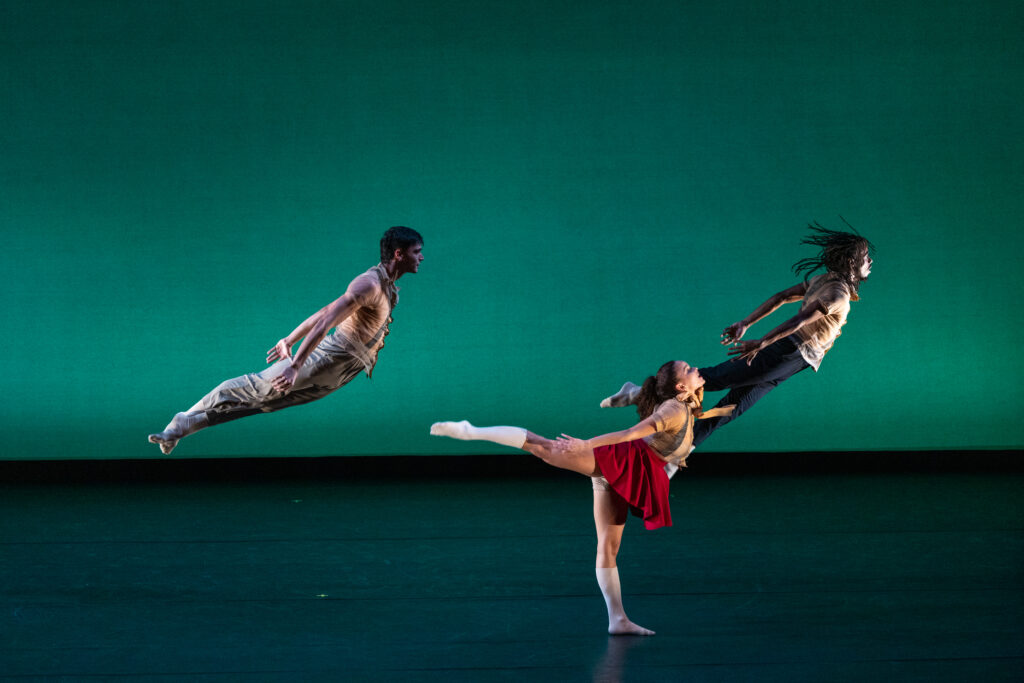

The Mark Morris Dance Group returns to Boston with Morris’ evening-length work, The Look of Love at Emerson Cutler Majestic Theatre from January 23 through January 26. The piece is a wistful and heartfelt homage to the chart-topping hits of Burt Bacharach, a towering figure of popular music, newly arranged by jazz pianist, composer, and MMDG musical collaborator Ethan Iverson. Bacharach’s melodies and unique orchestrations soar with influences from jazz, rock, and Brazilian music. The stage comes alive in a powerful fusion of dance and music with an exceptional ensemble of vocals, piano, trumpet, bass, and drums, led by singer, actress, and Broadway star Marcy Harriell.

SAS: Is there an overarching philosophy or spirit that you bring to your choreography?

MM: I wouldn’t know. I’m the wrong person to ask. I have no philosophy. I mean I famously answered that in Brussels. ‘I make it up. You watch it. End of Philosophy.’

I meant it. It’s not a word thing. It’s a choreo-musical thing. It’s not a philosophy. It’s been my only job, and I‘ve been doing it for nearly 50 years. So, I’m not waiting to figure out what it is. It’s music and dance; that’s what I’m about. It’s vocal music a lot, and vocal music has lyrics. Whether it’s an opera or popular songs or whatever language, the music exists because of the text.

So in the case of Hal David and Burt Bacharach meets Dionne Warwick, that’s a fabulous, brilliant combination of those things, and then I do like I would with Schumann or Handel or anything, I work with the music on its own terms. It’s always the same, in that I’m always working from music.

SAS: So what was it about the Burt Bacharach music and oeuvre that appealed to you?

MM: What happens is that good music lasts, and all good art is relevant to the people who find it appealing. The idea that it’s popular music and, therefore, not valuable is just utter nonsense. All good art is relevant to the people who find it appealing. It isn’t just written for just one person, it’s written for everybody, and it’s written from a particular point of view.

A lot of popular music fades away. So whether you know who wrote it or not, whether you know the words or not, whether you like it or not, you recognize certain bits of Burt Bacharach when you hear it. His music has endured.

He wrote from a huge range of points of view and it was all amazing music. Why Burt Bacharach? Why anybody’s music? Why would I choreograph it? I like it. I can’t work with shitty music, and I only work with live music.

In talking with Ethan Iverson about 15 years ago about music we’d been familiar with our whole lives, actively or not, music that was ‘in the air,’ Burt Bacharach’s name came up, and we thought, ‘Well, sure. Let’s do this.’

SAS: He wrote so many songs, how did you decide on the ones you chose and how did you decide on the order in which they appear?

MM: First of all, Ethan Iverson (who was my music director for a number of years long ago and whom I’d worked with before on “Pepperland,” the evening-length choreography and arrangement of Beatles music to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band album) and I listened to Burt’s music. We each picked our favorite songs. We also knew we didn’t want a whole bunch that were similar in style, tempo, or key.

In meeting with Burt, he gave us full approval and loose reins for the arrangements. When we got the rights, Ethan started arranging and I started choreographing. The very last thing was what order they would be in, and it went almost right up to opening night before we had the exact order because of the way I choreographed and the way they fit together according to key signature or rhythm or familiarity. I didn’t want it to be just a jukebox.

That’s the fun part, but it was a lot of hard work and we have now been performing it for a few years. It lives on and it’s really great.

SAS: What is The Look of Love about?

MM: The songs are all about love. Some are terribly sad, but many are upbeat. There’s optimism, but there’s also realism. They’re very profound songs. We don’t change the show performance to performance, but there are pockets of improvisation like there is in anything live, but it’s the same text and the same piece every night.

That’s why, if you go early (in the run), you can go back and see it again. That’s the live aspect of it, and there’s nothing better than that.

We haven’t been to Boston for six years! Covid was four and a half of them, but it’s been a while and we have an audience in Boston, we just haven’t been able to go for a long time, so we’re really happy to be back.

SAS: Your designer is the great fashion guru Isaac Mizrahi. How did that work?

MM: Isaac and I work together a lot. We’re very close friends. We’re both busy and we don’t work together that often. I knew that he was the right person for this, and so did he. We start with the music, which is how I start with everyone (lighting, design, costumes and music). I send Isaac the playlist of what I think is going to be the music long before we even start. He gives me some designs, and we talk about them and change them or not. It doesn’t start with a finished dance and then we add on to it. It’s pretty organic right from the starting gate.

That’s the way I like to work. It’s more thorough and it’s a collaboration. I’m in charge ultimately, but I listen and we participate or fight and it’s good. I don’t work with a lot of different people. I have a small roster of collaborators and it’s familiar in the sense that we don’t have to lie. We might say, ‘That’s the ugliest I’ve ever seen,’ or ‘That’s boring,’ or even, ‘That’s the greatest thing I’ve ever seen.’ That happens too sometimes, and it’s nice.

It’s friendly, but we’re pretty honest.

SAS: A lot of these songs are hits from long ago that younger audience members might be totally unfamiliar with them. Any thoughts about that?

MM: If you go see the show because you’re curious, and you can afford a ticket, that’s great. There’s no lesson to be learned from the show. It’s been very successful, and not just with seniors who, unfortunately, start singing along. The musicians start to play “Alfie,” and everyone goes, ‘Ohhh….’

This music is part of American folk ways now. Bacharach is part of the American Songbook.

SAS: Do you plan to keep doing what you’re doing? What next creative itch are you looking to scratch?

MM: I’m working on several things already. It’s been a very difficult period for everybody. I have a piece that will be premiering in early April, so I’ve been working on that all the time we’re not on the road.

This is my only skill. I’m going to do it til I can’t. One thing, I’m making up dances for after I don’t choreograph, after I’m dead or incapacitated. It’s a project called “Dances for the Future.” I have several pieces that are in the can, as they say, they’ve been choreographed, there are designs and notations and we’re going to keep them until I can’t make up dances anymore and then we’ll release them one a year for as long as we can do that. It’ll be a world premiere out of boredom, which I think is a fabulous, morbid idea.

I’m also working on a piece called “Moon” for a small festival in April commissioned by the Kennedy Center and inspired by the Golden Record on the 1977 Voyager.

SAS: Anything else you want to riff on?

MM: The Look of Love is not performed all that frequently. We don’t tour it for six weeks to five cities, it’s 3-5 shows and then it might weeks or months before we do it again. We re-rehearse it and buff it up and it’s a bit different and more confident and swings better every time we bring it back. It doesn’t change, but the tone and the ease with which we can present it is reassuring; it means we are performing it more, and we’re getting back in the hang of it.

For a YouTube preview of The Look of Love, click here. For tickets and information, go to: https://www.globalartslive.org/events/list-events