Moonbox’s ‘Crowns’ Raises the Roof

By Shelley A. Sackett

In Crowns, playwright Regina Taylor’s paean to the Black women who held their families, churches and communities together, gospel music, fanciful hats and swanky dresses take center stage. For 90 intermission-less minutes, this jukebox musical rocks the intimate Arrow St. Arts with two dozen songs and a narrative that traces the history of Blacks in America, from slavery to the Jim Crow south to the Civil Rights movement to present-day Black-on-Black violence in Brooklyn’s tougher neighborhoods.

These eras of Black history are not strung together by the play’s thin plot, but rather by the hats that Blacks have consistently worn, from African traditional headdresses to the most elaborate Church Lady hats to spangled, messaged baseball caps. Hats are connective tissue, and the collective spirit of the women who wear them has kept them all afloat. “Hats are a very African thing to do,” Mother Shaw (Mildred E. Walker), a congregant and our titular guide, announces. “All God’s children got a crown.”

They all also gotta have music, and the members of the cast (with keyboards by David Freeman Coleman and drums by Brandon Mayes) belt out song after song with such power and flair that it feels more like the gospel tent at New Orleans Jazz Fest than a midsize theater in Cambridge.

The performance begins with drumbeats and an African chant, “Eshe O Baba,” a Yoruba praise song that is considered worshipful. (Surtitles are helpful for identifying the speaker and providing a transcription of the lyrics, especially where so much of the dialogue occurs in song.) The cast sashays down the aisles as if they are models on a runway, dressed to kill in sequins, stiletto heels and, of course, hats. They pause and pose, reveling in the oohs and aahs. All the while, they sing a gospel song that has the audience smiling, clapping and dancing in their seats.

Baron E. Pugh’s simple set literally sets the stage as a church pulpit. Four pillars and two spot-lighted sculptural stands of hats flank a draped pulpit. The audience sits in a semicircle, invoking pews. There is even a Hymnal on the audience seats, with the words to many of the songs.

The storyline’s focus is on Yolanda (Mirrorajah, sadly miscast), Mother Shaw’s granddaughter, who was sent by her mother from Brooklyn to the south to live with her after her brother was shot to death. She is a complete stranger in a strange land, her hat of choice a baseball cap, her braided hair studded with bright beads. She hardly presents as potential “church lady” material.

Mother Shaw brings Yolanda up to speed as the cast sits as if in church, with their backs to us. She explains that during slavery, laws prohibited slaves from gathering except to attend church. After slavery ended, church was still THE place where Blacks could see and be seen. If you owned anything you wanted to be noticed — especially ladies’ hats — church was where you wore it. Gospel music and hats both have special powers, but hats also come with a list of do’s and don’ts.

As the houselights rise and lower, each woman comes forward to tell her story. Mother Shaw describes how her hat collection was the catalyst that empowered her to confront her husband when he tried to prevent her from buying more. She informed him that not only were her hats her property, but so was the money she earned and half the house. Mabel (Cortlandt Barrett) explains that there is a certain way to hug a woman in a hat. There are also “Hat Queen Rules” which must never be broken. Hats are passed on as family heirlooms and legacies, and a daughter has her mother buried in her favorite hat (“Lord, when I’ve done the best I can, I want my crown,” sings Velma (Lovely Hoffman)). Jeanette (Janelle Grace) and Wanda (Cheryl D. Singleton) round out the women; the character named Man (Kaedon Gray) plays all the male parts, minor supporting foils to the women.

The only time the women ever removed their hats, we learn, was during a protest march, but they were firmly reaffixed by that Sunday.

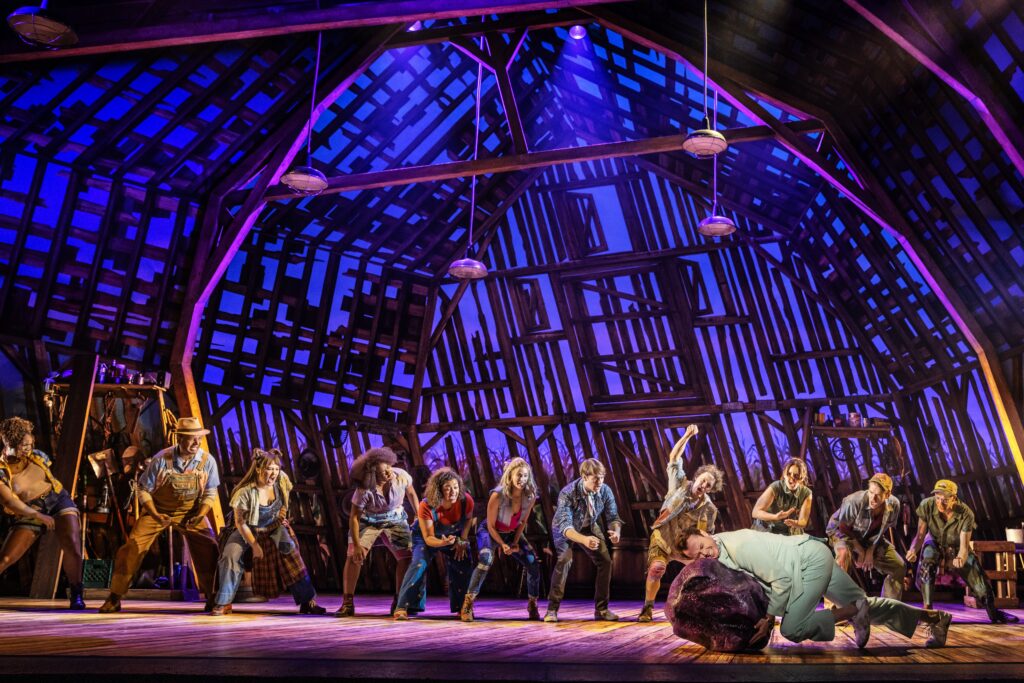

Eventually, Yolanda “gets” what the women are trying to teach her, and she embraces them and the church, but the snippets of her journey are really just a means to transition from song to song. In “That’s All Right,” the full ensemble raises the roof, dancing in a circle on the stage. The mixture of gospel, jazz, blues and traditional songs is a fabulous, curated playlist.

Barrett, as Velma, is a real knockout, and not just because of her flaming red dress and matching hat. She has a prodigious set of pipes and both poise and attitude. It’s hard to believe that she is only a sophomore at the Boston Conservatory. Hoffman, as Velma, soars in “His Eye Is On the Sparrow” and Walker, as Mother Shaw, is terrific, her strong voice both grounding and uplifting.

Although each actor has a chance to solo, the strength of the production is as an ensemble piece. Director Regine Vital has managed to delineate distinct individuals (E Rosser’s magnificent costumes help) while also creating a blended cast that seamlessly supports and complements each other.

Clearly, you don’t attend Crowns for its narrative arc. But if you enjoy extraordinary inspirational music, snapshots of everyday lives lived by everyday people and, of course amazing hats, then Crowns is right up your alley. It is also one helluva raucous good time!

Moonbox Productions presents ‘Crowns’ by Regina Taylor, adapted from the book by Michael Cunningham and Craig Mayberry. Regine Vital, Director. David Coleman, Musical Director. Davron Monroe, Associate Director. Kurt Douglas, Choreographer. Isaak Olson, Lighting Designer. Baron E. Pugh, Scenic Designer. James Cannon, Sound Designer. Danielle Ibrahim, Props Designer. E Rosser, Costume Designer. Schanaya Barrows, Wig Designer. At Arrow Street Arts, 2 Arrow Street, Cambridge, through May 4, 2025.

For more information, visit https://www.arrowstarts.org/