Emerson Colonial’s ‘Mean Girls’ Is More Meh Than Mean

By Shelley A. Sackett

Tina Fey’s Mean Girls has certainly milked its appeal. When it first appeared in 2004 as a film starring Lindsay Lohan, Rachel McAdams and Amanda Seyfried, it was a runaway hit. Its 2018 transformation into a Broadway musical fared less well and the 2024 remake of the film fared even worse.

Which brings us to the 2025 theatrical musical version that played at Emerson Colonial Theatre recently. Suffice it say, the newest iteration did nothing to reverse Mean Girls’ downward trajectory. Unless, that is, you happen not to have been born in 2004. In that case, (as was evidenced by the hordes of pink-clad teens and twenty-somethings at a Wednesday evening performance), the latest musical version was just what the Minister of Culture ordered.

Plot-wise, not much has changed. Teenage Cady Heron (a tentative Katie Yeomans) was home-schooled in Africa by her scientist parents. When her family moves to the suburbs of Illinois, Cady is jettisoned into the public school jungle, where she gets a quick primer on the cruel, tacit laws of popularity that divide her fellow students into tightly knit cliques from Damian (a terrific Joshua Morrisey) and Janis (Alexys Morera, also very good). But when she unwittingly finds herself in the good graces of an elite group of cool students run by the Queen Mean Girl, Regina (Maya Petropoulos), and dubbed “the Plastics,” Cady is initially seduced by the allure of being a member of the “in” crowd.” Once she realizes how shallow, and, well, mean, this new group of “friends” is, she rebefriends Janis and Damien and exposes Regina and her acolytes for who and what they really are.

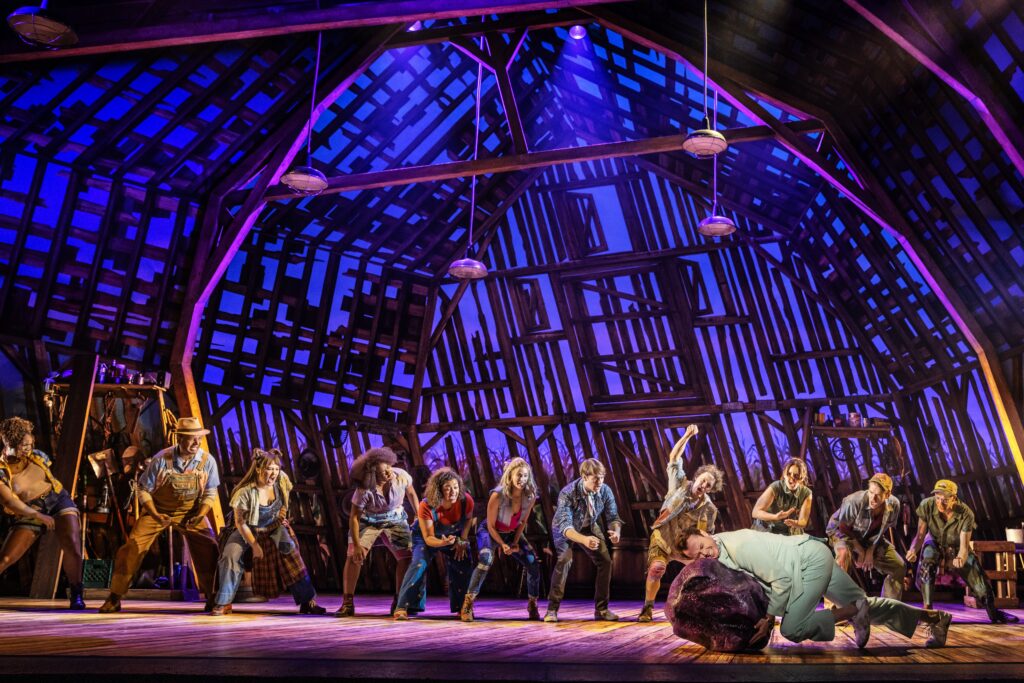

Between opening and closing curtains are 20 musical numbers that take us on a trip through the trials and tribulations of high school with all its unspoken rules and regs, hierarchies, and, of course, sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll. Playing multiple roles, Kristen Seggio is a standout as teacher Ms. Norbury, bringing welcome talent and presence to the stage. Scott Pask’s set design is clever and engaging (especially the use of desks on rollers), and John MacInnis’ choreography occasionally shines, especially in the tap number and the use of trays for the lunch scene. But unfortunately, for the most part, the young actors (almost all are debuting in their first national tour) swallow a large percentage of their lines and lyrics, making an at times tedious production all the more so.

There are, to be fair, some high moments, especially during any musical numbers with harmonies. The show opens strongly, with scene-stealer Morrisey and Morera in fine voice and form. Kristen Amanda Smith is effective and (almost) endearing as an on-again, off-again member of Regina’s posse (plus she has a wonderful voice with which she projects and enunciates). As Karen, the airhead blond Regina worshipper, Maryrose Brendel brings a surprising freshness and nuance to a character who is plastic in more than group membership.

At the end of the day, perhaps Al Franken, Fey’s fellow Saturday Night Live member, summed up Mean Girls’ message to teenagers struggling with the pain of social cliques best. As his beloved character Stuart Smiley would say, “I’m good enough. I’m smart enough. And, doggone it, people like me.”

‘Mean Girls.’ Book by Tina Fey. Music by Jeff Richmond. Lyrics by Nell Benjamin. Based on the Paramount Pictures film “Mean Girls.” Directed by Casey Cushion. Choreography by John MacInnis; Scenic Design by Scott Pask; Costume Design by Gregg Barnes; Lighting Design by Kenneth Posner; Sound Design by Brian Ronan; Music Direction by Julius LaFlamme; Orchestrations by John Clancy; Music Coordination by John Mezzio; Hair Design by Josh Marquette. Presented by Emerson Colonial Theatre, Bolyston St., Boston. Run has ended.