By Shelley A. Sackett

Counterpoint, the 75-minute collaboration between pianist and composer Conrad Tao and choreographer and dancer Caleb Teicher, is a magical journey that explores the interplays between two seemingly divergent art forms — tap and solo piano.

Yet, these two virtuoso performers, who met as teenagers and immediately hit it off artistically and personally, perform alchemy to fuse their music and dance and conjure something unique and thrilling. Their exploration of connection rather than divergence results in a program that feels more like eavesdropping on a private performative conversation than attending a formal concert.

Being in the audience (almost) equals the fun and exuberance they exhibit on stage.

“Counterpoint,” is defined in music as the art of playing melodies in conjunction with one another according to fixed rules. In Counterpoint, it becomes a discussion or conversation between Tao and Teicher’s different art forms of music and dance, between their different instruments of piano and tap and between the different traditions that have been attached to each.

It is also an opportunity for the two to improvise, bringing fresh energy to familiar pieces that span a wide selection of musical genres. Their back-and-forth brims with theatricality, harmony and raw rhythm.

Stylistically, the program of 11 pieces meanders from J.S. Bach’s “Aria” from his Goldberg variations to Art Tatum’s “Cherokee,” a Honi Coles and Bufalino Soft Shoe, Brahms’ Intermezzo in E Major, Gershwin’s iconic “Rhapsody in Blue” and back again to Bach’s “Aria.” There is a Schoenberg, Mozart and Ravel along the way, and even two exceptional original pieces, one that changes with each performance and is titled “Improvisation.”

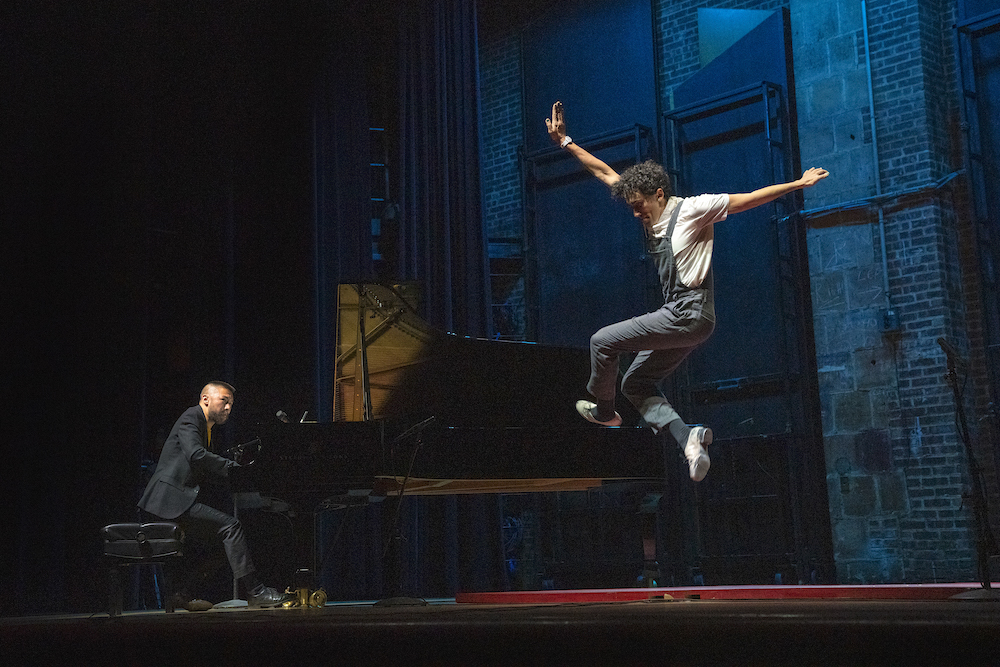

The set is simple: a shiny piano, tap platform, and chair. At first, Teicher just sits as Tao’s soulful rendition of the Bach aria fills the hall. When Teicher stands, his white, short-sleeved jumpsuit is mirrored in the piano’s sheen. He slowly, thoughtfully begins to drag his feet, transitioning to graceful almost slow-motion ballet moves and eventually breaking into a whimsical introduction to the clickity-clack of the tap element. It’s a perfect way to start this quirky tête-à- tête between pianist and dancer.

“Improvisation” at Saturday’s matinée started with a slow interchange between dissonant piano chords and the soft scarping of Teicher’s shoe. Both increase in intensity almost to the breaking point, yet the two rhythms complement, rather than compete with, each other.

Teicher gives the audience a glimpse of his prodigious stage presence with the theatrical facial expressions and body languages he brings to “Cherokee.” A mere tilt of the head, the whisper of a wink and a smile, silently speak volumes. With his introduction of “Coles and Bufalino Soft Shoe,” he is also the charming emcee, genuinely interested in having the audience join in on the fun.

“Swing Two,” an excerpt from the duo’s Bessie Award-winning “More Forever,” exemplifies the concept of Counterpoint, or two melodic lines interacting. Tao’s piano is as rhythmic as Teicher’s dancing, which is as tuneful as Tao’s keyboard.

The expressive, easily accessible “Rhapsody in Blue” earns the pair an interruptive standing ovation. Its happy fusion of jazz and Broadway and the dramatic blue lighting are perfect backdrops for Tao’s vivid, emotive piano and Teicher’s expressive dancing. They both display playful attitude in this piece. When Teicher strikes a pose or seems to float on the tip of his shoe, there is an impish, elfin hammy element to him that makes his performance all the more endearing.

Both have their solo moments too, Tao in the Schoenberg and Ravel pieces and Teicher in the Bufalino soft shoe and the magnificent Mozart “Alla Turca,” where he demonstrates tap’s vocal range while exuding joy and adorability. Although there is no piano accompaniment, Teicher’s masterful dancing creates an imaginary score which he encourages the audience to try to access. “When you hear these sounds and see me gesture and dance, use your imagination to create a story and fill in the blanks,” he advises. “Watch it again and think about what you see and feel.”

The program ends with an “Aria” bookend, and we have come full circle, but so much richer for the experience.

Celebrity Series of Boston presents Caleb Teicher & Conrad Tao in ‘Counterpoint.’ At the Boston Arts Academy Theater, Feb. 7-8.