Photos by Hawver and Hall

‘Wonder’ — Book by Sarah Ruhl. Music and lyrics by A Great Big World (Ian Axel and Chad King). Directed by Taibi Magar. Choreographed by Katie Spelman. Music supervision by Nadia DiGiallonardo. Presented by American Repertory Theater at Loeb Drama Center, 64 Brattle St., Cambridge, through Feb. 8.

By Shelley A. Sackett

Middle school is widely recognized as one of life’s toughest crucibles, a time of major physical, emotional and social change. A petri dish of hormonal upheaval, intense social pressures and increased academic demands, it has all the ingredients for an emotive perfect storm.

Now imagine navigating these turbulent waters as a boy with facial differences facing transition from homeschooling to private school, where he will, for the first time, have to mix with other kids, and that perfect storm suddenly lurks as a tsunami of epic proportions.

This is the premise of Wonder, the new coming-of-age musical drama débuting at American Repertory Theater. Based on R.J. Palacio’s best-selling 2012 young adult novel, Sarah Ruhl’s play tells the story of Auggie Pullman, a boy born with Treacher Collins syndrome, a rare genetic disorder that interferes with the development of facial features.

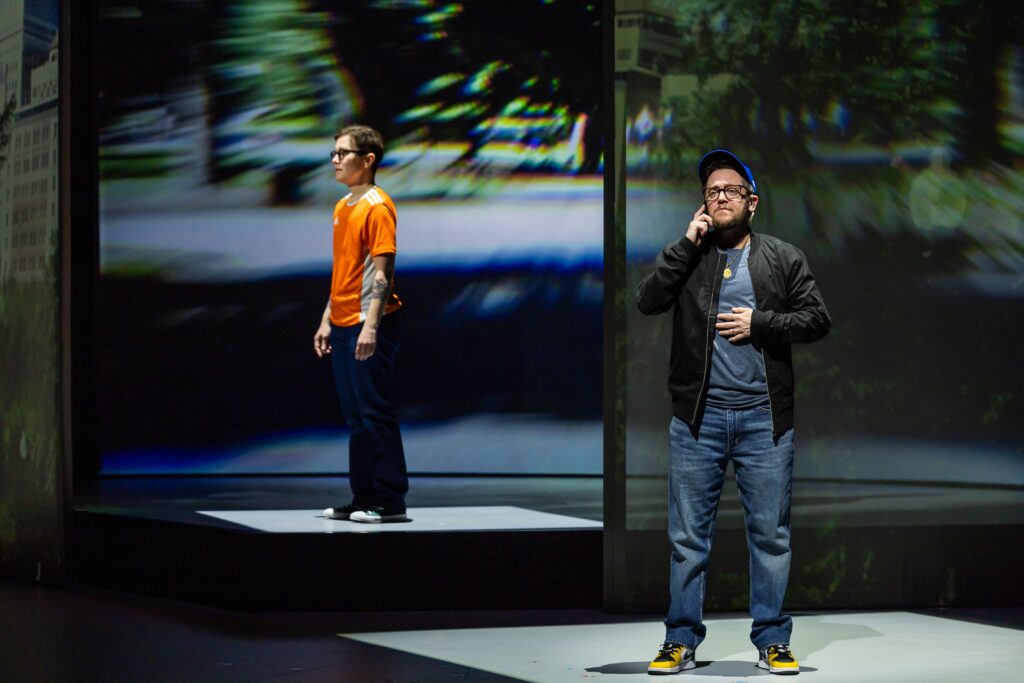

Auggie (Garrett McNally last Friday night. He shares the role with Max Voehl) is a typical 12-year-old in many ways. He straddles childhood and adolescence. His bedroom is still that of a little boy with its bed shaped like a spaceship, and he has an imaginary friend, Moon Boy (Nathan Salstone, a talented standout), who provides protection and companionship.

Auggie also asks more grown-up, bigger picture questions, wondering, for example, why he was created as he was. He longs to be ordinary, yet by the play’s end, it is his extraordinariness that elevates both Auggie and everyone around him.

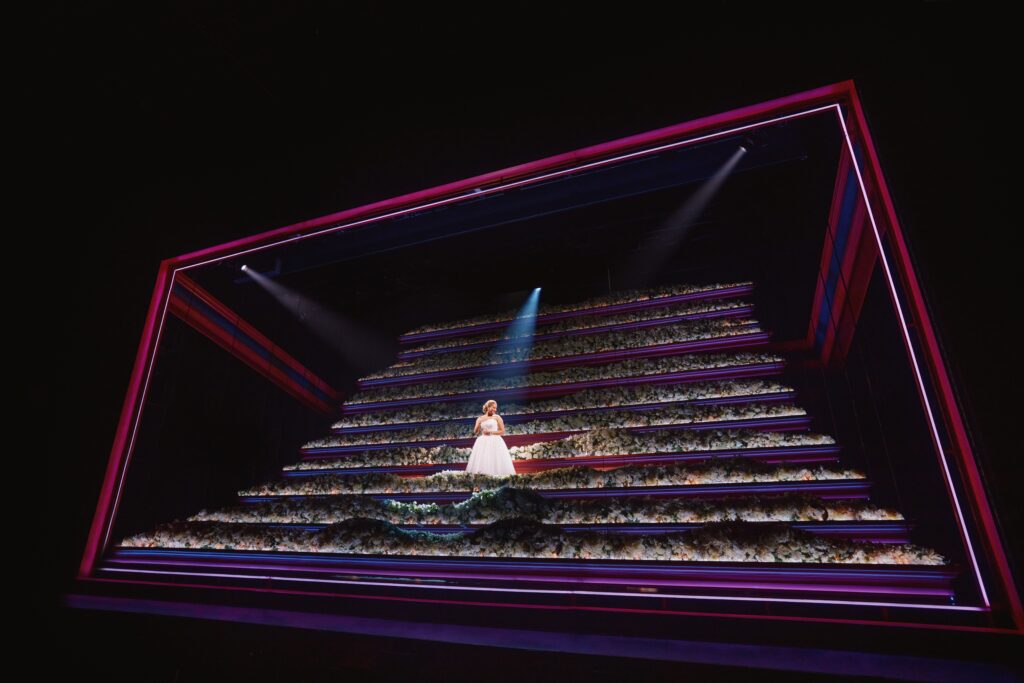

Matt Saunders has created an elegant, simple set of moving panels with a patchwork quilt of lighted squares that reflect the mood as they change from celestial blues to red and yellow to shades of pastel mauves (Lighting by Bradley King). Songs by pop duo A Great Big World (Ian Axel and Chad King) are funny, catchy and upbeat with lyrics that reveal their characters’ inner lives and fill us in on important details. (Unfortunately, the band too often drowns them out).

The splashy opening number, “3-2-1 Blast Off!” showcases the charismatic Salstone and introduces us to Auggie. “You Are Beautiful,” a song celebrating Auggie’s unique beauty and strength, recognizes his inspiring journey of 28 surgeries and the “scars tell a story of a boy who’s strong,” making him a “wonder.”

Auggie’s parents, Nate (Javier Muñoz) and Isabel (Alison Luff) have decided it’s time to wean Auggie off homeschooling and shift to the private co-ed Beecher Prep. Isabel needs time to herself and Auggie’s intellectual capacity and needs exceed what she can provide. He needs to integrate with other kids (and, as importantly, they with him).

Auggie is terrified. His experiences with other kids have been disastrous. They can’t get past how he looks, reacting with fear, disgust and ridicule. Eventually, he relents, but not until Moon Boy promises to accompany him and his parents agree to let him bring his space helmet.

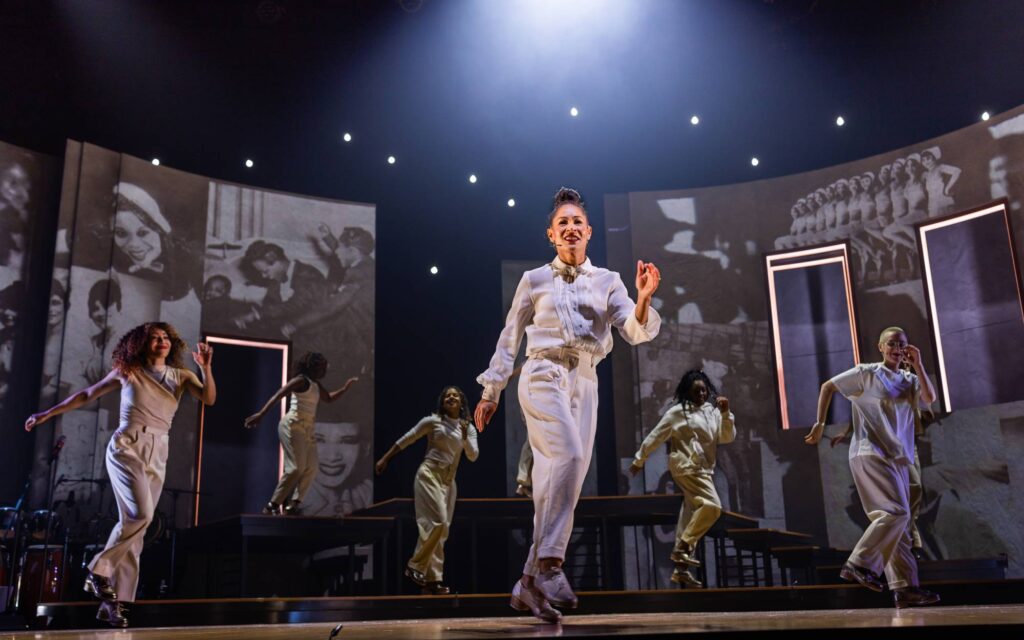

The Beecher Prep scenes are where the play shines, with a near-perfect blend of choreography (Katie Spelman), ensemble singing, and terrific performances by its peppy teachers (Pearl Sun and Raymond J. Lee). Director Taibi Magar elicits crisp performances and makes effective use of the concentric rotating circles on stage.

All is not roses for Auggie, however, and bullying becomes a big part of the story. Middle school brings out meanness (aka insecurities) in some kids, and Auggie’s facial difference provides both a focal point and a bull’s eye.

The play’s strength and interest lie in its exploration of other characters’ perspectives. Auggie’s sister Via (Kaylin Hedges) has played second fiddle to her brother since the day he was born. “Hospital waiting rooms were our playground,” she explains. Because her life is so much smaller than his, no one (especially not her parents) pays attention to her. Nonetheless, she is fiercely devoted to her little brother. There are two Auggies, in her opinion — “What I see. What others see.”

As other characters take center stage, we see that everyone struggles, even the bullies. There are enough plot curves to provide interest without the need for heavy lifting, but the lifeblood of Wonder is its message of kindness, empathy and hope.

Auggie’s mother gets the ball rolling, telling Auggie she sees only the wonder and beauty in him, even in his scars. Auggie takes that ball and runs with it, as do the school’s principal, Mr. Tushman and, eventually, all his classmates. They learn what it’s like to walk in another’s shoes, to choose being kind over being right, to value harmony and heart over war and might. Lyricists Axel and King are never preachy nor syrupy, and their lessons resonate all the more because of it. “Auggie can’t change how he looks,” the students are told, “but we can change how we look.”

Magar, in the director’s notes, eloquently echoes the thoughts of many as we start the post-equinox ascent from our darkest to lightest days.

“I hope Wonder meets you wherever you are—whether you’re searching for awe, for hope, for connection, or simply for a story that believes in the goodness we’re capable of. Theater may not change the world the way teachers and politicians do, but it can change us. It can open something. It can remind us of who we want to be. May this performance fill you with a little more wonder—and a little more hope.”

Amen to that.

For more information, visit https://americanrepertorytheater.org/