By Shelley A. Sackett

A corner booth, fancy fare and tasty conversation — who doesn’t remember the cult frenzy caused by Louis Malle’s 1981 110-minute film that enchanted audiences, defied pigeon-holing and raised the bar on the “art” referred to as conversation?

This unconventional film should have been all but unwatchable. After all, it is simply a cinema verité version of a conversation between playwright Wallace Shawn and André Gregory, a well-known experimental theater director who seems to have dropped off the edge of the planet and whom Shawn has been trying to avoid for years.

For some, the film actually was unwatchable, and it is not to that audience that Harbor Stage’s theatrical version is geared. For those, however, who found the film charmingly quirky, the production at BCA Plaza Black Box Theatre is right up your alley.

Adapted by Jonathan Fielding (who plays – and looks like – Wally Shawn) and Robert Kropf (ditto for André Gregory), the play brings its audience through the celluloid keyhole right into the cozy, ritzy Manhattan restaurant. Evan Farley’s terrific scenic design channels the film’s setting with chandeliers, chic sconces and rich red leather upholstery. Four gilt-framed mirrors line the walls above the booth, a stroke of brilliance that allows the audience to witness the characters’ actions and reactions from multiple angles and perspectives.

Breaking the fourth wall from the get-go as narrator and soul bearer, Wally lets the audience eavesdrop on his internal monologue Woody Allen-style. “Asking questions always relaxes me,” he confides, setting the tone for the questions about life, death and everything in between that will occupy the next 90 intermission-less minutes.

The two meet at the restaurant and it is immediately clear that Wally is a fish out of water with the swanky menu (which, in an aside, he confesses he can’t translate) and even swankier server (a Lurch-like Robin Bloodworth). André is comfortably in his element and, with infinitesimal prodding, launches into an epic monologue that is as shocking in its length as in the fact that it is neither boring nor obnoxious, despite André’s obsessive fascination with all things André.

He tells Wally that he strives to lead his life as improvisational theater, and his journeys through the Sahara desert to Tibet to the forests of Poland are surreal and capture Wally’s attention. (In truth, Wally may be less captivated than relieved to be cast as the silent listener). Nonetheless, André’s insistence on waking himself to the true meaning of life and hurtling through the emotional cosmos contrasts perfectly with Wally’s grounded, simpler take on what it means to be a human being.

For André, a complacent life is a squandered life. Wally, on the other hand, not only sees nothing wrong with comfort but actively seeks it out. He’s just trying to survive, he admits, and unapologetically takes pleasure in such simple matters as errands, responsibilities, and Charlton Heston’s autobiography. He can’t understand why André is so wrapped up in figuring out what makes a hypothetical life worth living that he is unable to enjoy the details of his own life. Exasperated, Wally blurts out, “I don’t know what you’re talking about,” the truest words he’s uttered all evening.

When the two discuss theater and the responsibility of its creator to its consumer, things get more interesting and realer because Wally (finally) speaks up and disagrees with André. André insists that theater needs to show the audience a version of the world that is different from their reality, to take them to an extreme place that will shake and shock them into consciousness.

Wally believes that theater should connect people with reality and be enjoyable. People go to theater to be entertained and to relax, not to be confronted by existential crises. He is more perplexed by the challenge of eating quail (“God, I didn’t know they were so small”) than the quest for the answer to the meaning of life.

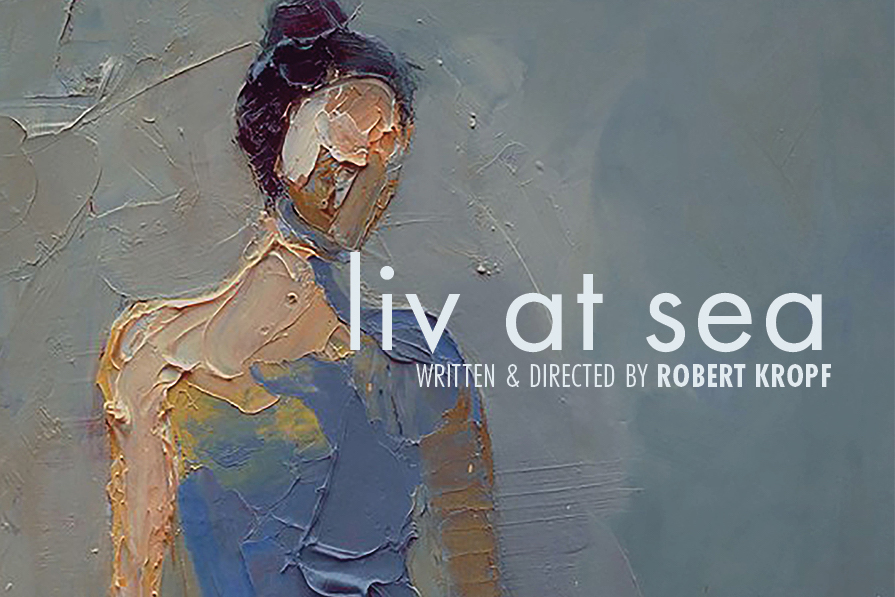

Even if all this verbosity, pompousness and navel-gazing turns you off, you might still consider seeing ‘My Dinner with André’ just to bask in the performances. Kropf is phenomenal as André, his cadence and gestures imbuing pages of monologue with simplicity and purposefulness. The tiniest flicker of an eye or tonal shift softens his character and exposes an interiority that prevents André from devolving into a shallow, two-dimensional showoff.

Fielding is the perfect foil. His Wally is a little nervous, a little frumpy and satisfied enough – for now. His facial reactions to André’s stories say more than pages of dialogue might; his slight self-conscious discomfort renders him all the more endearing. If the ordinary rules of life don’t seem to apply to André, Wally is only too happy to take up the slack, following the path of least resistance and most relief.

‘My Dinner With André’ – Based on the film by Wallace Shawn and André Gregory. Developed by Johnathan Fielding and Robert Kropf. Production Stage Management by D’Arcy Dersham. Scenic Design by Evan Farley. Lighting Design by John Malinowski. Produced by Harbor Stage Company, ‘My Dinner With André’ runs at BCA Plaza Black Box Theatre at 539 Tremont Street, Boston. Run has ended

For more information visit: https://www.harborstage.org/