By Shelley A. Sackett

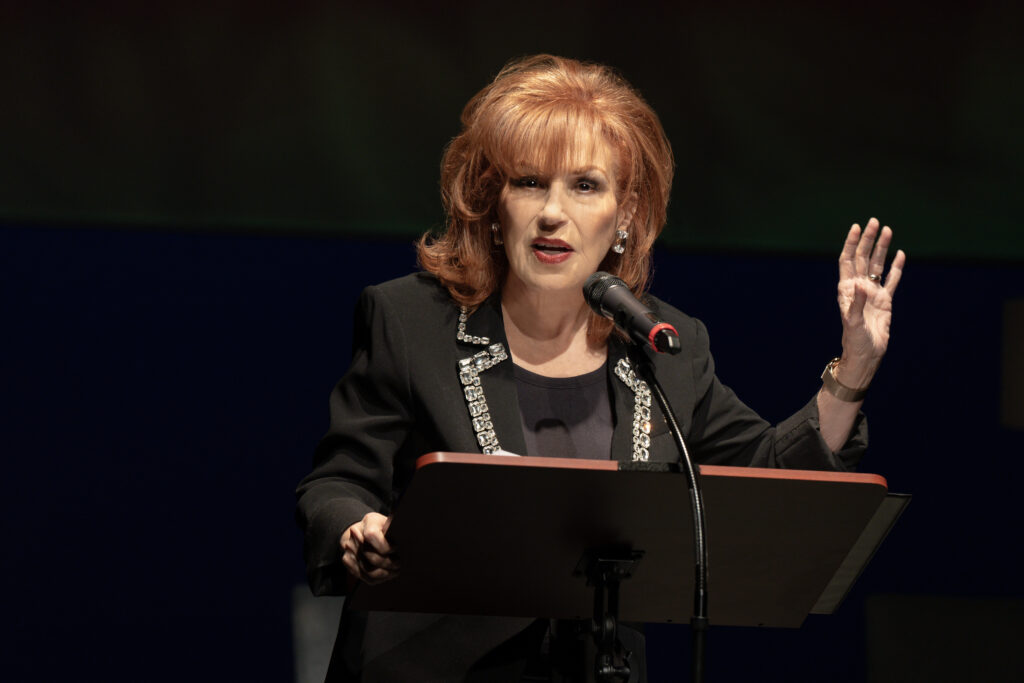

Joy Behar is familiar to fans of television’s ABC daytime talk show, “The View,” as the co-host with the comedic, acerbic wit. She won an Emmy Award in 2009 and is also known as a sharp-tongued, incisive stand-up comic.

With My First Ex-Husband, her fourth play that ran successfully off-Broadway and is now in production at The Huntington Calderwood through September 28, she will be known to Boston audiences as a playwright as well.

The idea came to her from her own divorce in the early 1980s. She and her girlfriends would get together and talk about their experiences. Wading through the painful, she also uncovered the humorous.

She decided (with permission, of course) to tape some of their conversations, eventually transforming them into a 90-minute Moth-like show of eight vignettes, read by a rotating cast of five, including Joy at select performances.

My advice: if you plan to see the show, make sure you are seeing it on a night when Behar is performing. The woman, at 82, is a pint-sized firecracker. As Rob Reiner’s mother ad-libbed in “When Harry Met Sally,” I’ll have what she’s been having. Her enthusiasm and energy are as contagious as it is a delight to witness. That she is 82 is both an inspiration and an aspiration.

The full cast of stars from theater, television, and film also includes Veanne Cox, Judy Gold, Jackie Hoffman, and Tonya Pinkins.

The stage is set like ‘The View,” with four seats set in front of luscious red velvet curtains. “My First Ex-Husband” hangs over the stage, framed like a valentine. The microphone and reading stand host each reader in turn.

“Hello, Boston!” Behar calls as she walks onto the stage. The crowd last Sunday, clearly fans, greets her with adoring applause. “How many of you are divorced?” A sea of hands wave. She pauses with expert timing before following up with, “How many of you would like to be divorced?”

She begins by describing the state of divorce in the U.S. There has been an uptick in divorces of those over 50. “The only people under 50 getting married are gay people,” she jokes. Seriously, she continues, she was intrigued by this statistic. She started interviewing women about why they wanted to get divorced. “Women couldn’t wait to tell me their stories,” she says.

The men, not so much.

All the stories in My First Ex-Husband are true, she explains, adding that her next show will be titled My Next Ex-Husband.

Tonya Pinkins is first to the podium. A renowned theater actress, she is a three-time Tony nominee, winning the award in 1992 for her performance as Sweet Anita in Jelly’s Last Jam. The title of each monologue appears above the stage. Hers is “Where You At?” Her delivery is full-throated, emotive, and dramatic.

Next up is Vivien Cox, who has received a Special Drama Desk Award for “Excellence and Significant Contributions to the Theatre” and an Obie Award for “Sustained Excellence.” “Show me a man who loves a plump woman, and I’ll show you a foreigner,” she deadpans. “Walla Walla Bang Bang” features Judy Gold, a stand-up comedian, actor, author, TV writer, and activist who The New York Times dubbed, “an underappreciated gem of the New York comedy scene.”

Lanky, tall, bespeckled and with a head of bouncing blond curls, she is the opposite of Cox’s prim, proper and controlled persona. The personalities and presentations of each actress complement and complement each other visually, stylistically, and delivery-wise, keeping the staging from getting stale.

Gold’s story is about being dragged from her dream of an East Side high-rise in New York City to a farm in upstate New York by a husband whom, unsurprisingly, she later divorces.

Behar, however, is the most effective, her stand-up chops on full display. Each actress gets another bite at the apple, with a total of eight stories. Most are funny, all are unfiltered, and the audience leaves a little lighter than it arrived. Who, after all, can’t use a good laugh these days?

‘My First Ex-Husband’ — Play by Joyce Behar. Directed by Randal Myler. Presented by The Huntington Selects. Produced by Caiola Productions and Cyrena Esposito. At The Huntington Calderwood, 537 Tremont St., Boston, through September 28.

For more information, visit Huntingtontheatre.org