By Shelley A. Sackett

Pierre Carlet de Marivaux’s “The Triumph of Love,” which premiered in 1732 and is at The Huntington through April 6, is like a trifle dessert, with light spongey layers of raucously funny deceptions, disguises and mistaken identities soaked in a sherry-spiked pastoral period set design. Instead of the traditional alternating tiers of sweet jams and custard, however, Marivaux has substituted a bitter concoction of calculated cruelty and manipulation. The end result is a sugar-coated confection that leaves a very bitter taste in the mouth.

Stephen Wadsworth’s definitive and sparkling translation is chock-full of clever double entendres and contemporary plays on words that prevent Marivaux’s commedia dell’arte from getting stuck in 18th-century French linguistic mud.

A hectic first scene gives the lay of the land. We meet two women, loosely disguised as men, in the country retreat setting of a manicured garden. Princess Léonide (an excellent Allison Altman) and her maid, Corine (Avanthika Srinivassan), quickly bring the audience up to speed on who they are, why they are there, and what they plan to accomplish.

Léonide (incognito as the man Phocion) is the princess of Sparta, but only because her uncle stole the throne from the rightful king (who, to make matters more complicated, had kidnapped the rightful king’s mistress). While on a walk in the woods, Léonide spotted the young man Agis (Rob Kellogg), who lives in the household of the old philosopher Hermocrates (a terrific Nael Nacer) and his spinster sister, Léontine (Marianna Bassham, perfectly cast). It turns out that Agis is the true prince and rightful heir to the Spartan throne. Hermocrates, a strict follower of Enlightenment tenets, rescued him and raised him in seclusion to embrace the safety of rational reason and spurn the dangers of the kind of romantic love that destroyed his parents.

Undaunted, Léonide vows to win Agis’ heart and restore him to power. First, though, she has to get past the brother and sister team of Hermocrates and Léontine. No problem for our wily and ingenious princess; she will simply get them both to fall in love with her so she can then use them in her pursuit of her true love.

All of which, through a series of tricks, treacheries and outright cons, she accomplishes. Employing a variety of alter egos and all her charm and quick-tongued-ness, she turns the heads of the stuffy Hermocrates, his desiccated old maid sister, and his virginal charge.

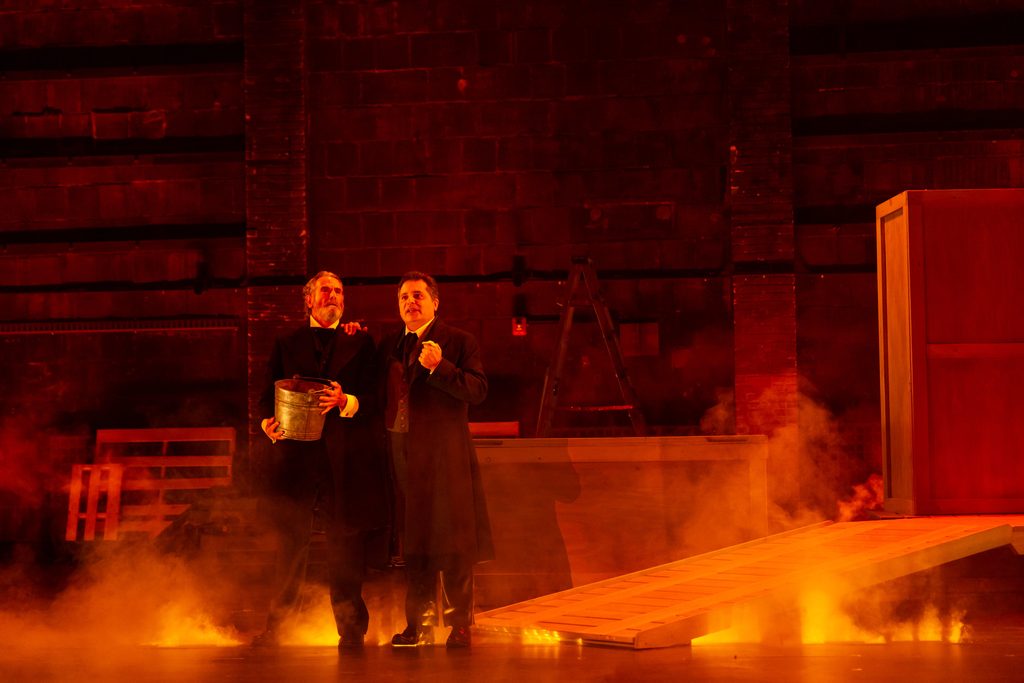

On its surface, ‘A Triumph of Love’ explores and ridicules the sharp lines drawn between the Enlightenment’s Age of Reason and the subsequent Romanticism movement, which focused instead on emotion, individualism, and the sublime. There are some great supporting characters, including Hermocrates’ servant, Harlequin (a delightfully spry Vincent Randazzo), and gardener, Dimas (Patrick Kerr), and some corny, rim-shot humorous one-liners. (“They are dresspassers,” Harlequin says of Léonide and Corine, and “Digression is the better part of a valet.”) Harlequin and Dimas are breaths of fresh air, and Randazzo’s entr’acte solos are wonderful diversions.

There is also a lot of meaty, thought-provoking dialogue about the meaning of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, especially when it comes to love. Marivaux isn’t afraid of exposing his characters’ seamier sides, and he asks some tough, smart questions about complicated philosophical issues.

Junghyun Georgia Lee’s classically elegant set and costume designs are spot on, as is Tom Watson’s hair, wig, and makeup design (special kudos for Nacer’s transformed pate!). Although the first act drags a bit, director Loretta Greco (and, therefore, her cast) find their footing in the second act, which flows more easily and naturally. As Léonide, Altman is a triumph, which is fortunate since she dominates nearly every scene during the production’s 135 minutes (one intermission). She never ceases to surprise and engage, no matter how contrived and repetitive the ruse, a masterly feat to be sure.

Yet, for all the romping and spoofing, there is an undeniable nastiness reminiscent of “Les Liaisons Dangereuses.” To try to change the minds of those stuck in the rigid rules of reason and logic, and advocating for a life of feeling and love by engaging in honest debate, is one thing. But proving your point that a life of passion is not only possible but preferable by tricking people to fall in love with you and then discarding them is just plain mean. Awakening a frozen heart to feeling and then condemning it to a life of philosophy without love not only proves the point that love is self-serving, hazardous and risky; it also raises an even bigger and more timely issue: can nefarious means ever justify the ends?

‘The Triumph of Love.’ Written by Pierre Carlet de Marivaux. Adapted by Stephen Wadsworth. Directed by Loretta Greco. Scenic and Costume Design by Junghyun Georgia Lee. Hair, Wig, and Makeup Design by Tom Watson. Lighting Design by Christopher Akerlind. Composer and Sound Design by Fan Zhang. Presented by The Huntington Theatre, 264 Huntington Ave., Boston through April 6, 2025.

For more information, visit https://www.huntingtontheatre.org/whats-on/the-triumph-of-love/