Shelley A. Sackett

While 2025 had its theatrical hits and misses, there was much to celebrate, especially among some smaller theaters presenting edgier and more provocative works. It was a varied year, with big, splashy musicals; sharp, intimate family dramas; and risk-taking, inventive productions that pushed the envelope on what we label “theater.” Once again, the vibrant greater Boston theater scene, with its stellar stable of directors, actors and creative production teams, blessed its patrons (and reviewers!) with an abundance of riches, for which we all should give thanks.

In descending order, my list is:

- Hamilton (Broadway in Boston)

A flawless production of the play that just keeps giving. Broadway in Boston’s production at Citizens Opera House was as good as it gets, from set design to actors to choreography and musical direction.

- Fun Home (Huntington Theatre)

Adapted from Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel memoir, the storyline follows a family’s journey through sexual orientation, gender roles, suicide, emotional abuse, grief, loss, and lesbian Bechdel’s complicated relationship with her tightly closeted father. A brilliant script and score and superb production elevated this potentially gloomy tale to one of the year’s top performances.

- The Glass Menagerie (Gloucester Stage)

Gloucester Stage effectively took the road less traveled in its presentation of the 80-year-old classic with an interesting and thought-provoking production that allowed the audience to experience Williams’ script anew through an exciting, hyper-focused and refractive lens.

- Man of No Importance (SpeakEasy)

There is so much to praise about SpeakEasy Stage Company’s ‘A Man of No Importance,’ director Paul Daigneault’s swansong production after leading the company he founded for 33 years, it’s hard to know where to begin. The ensemble of first-rate actors, musicians, choreography, set design, 20 songs, and brilliant directing were the shining constellation at the epicenter of this production that ends on an uplifting note, one that is as relevant and helpful today as it might have been in Oscar Wilde’s day..

- Our Class (Arlekin Players Theatre)

No one can take his audience on an emotional and artistic roller coaster like Igor Golyak, founder and artistic director of Arlekin Players Theatre & Zero Gravity (Zero-G) Theater Lab. With Our Class, he introduced us to characters we initially relate to and bond with, spun an artistically ingenious cocoon, and then told a tale that ripped our heart to shreds and left us too overwhelmed to even speak. The acting was indescribably sublime, each actor both a searing individual and a perfect ensemble member.

- The Life & Times of Michael K (ArtsEmerson)

In substance, Life and Times of Michael K tells the extraordinary story of an ordinary man. Adapted from the 1983 Booker Prize winner, written by South African novelist J. M. Coetzee, it details the life of the eponymous Michael K and his ailing mother during a fictional civil war in South Africa.

As adapted and directed by Lara Foot in collaboration with the Tony award-winning Handspring Puppet Company, this simple tale becomes the captivating and transportive production. Michael K. (and a cast of many) also happens to be a three-foot-tall puppet made of wood, cane, and carbon. “Must see” hardly does it justice; this is a groundbreaking pilgrimage into the multisensorial world of out-of-the-box theater.

This sunny, upbeat two-hander musical romantic comedy was as beguiling as it was impeccably acted, directed and produced. Unlike too many musicals these days, Two Strangers has a complicated plot and fetching music with lyrics that are Sondheim-esque in their conversational fluency and relevance. Add to that a smart, slick set, superb band, impeccable direction, and perfectly matched and equally talented actors for a full-blown fabulous evening of musical theater at its finest.

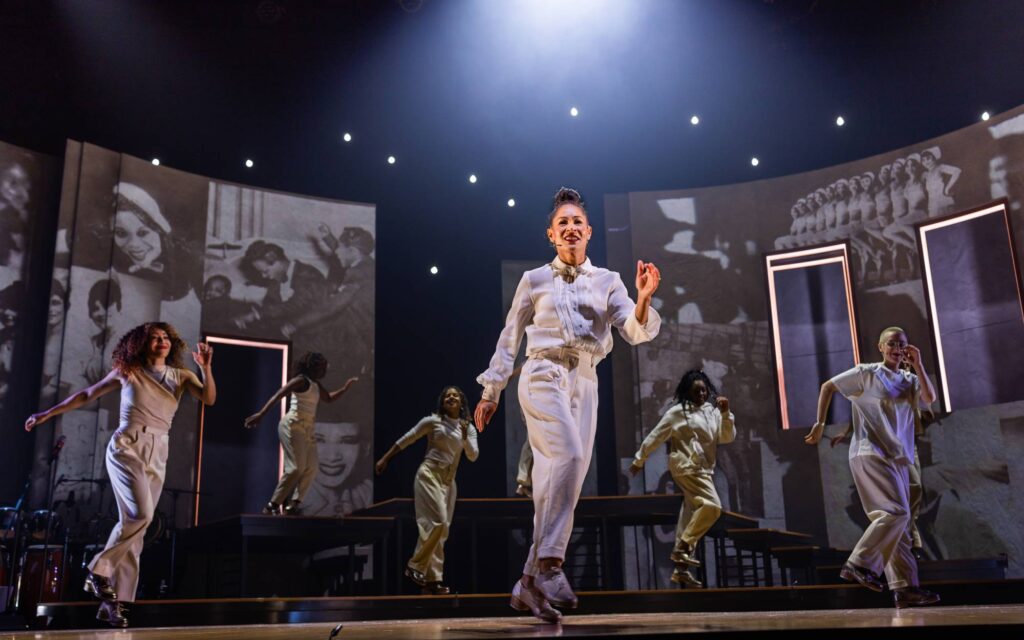

- Rent (North Shore Music Theatre)

NSMT is tailor-made for musicals with its theatre-in-the-round, signature creative set designs and talented casts. With Rent, the Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award-winning musical set in New York City’s East Village from 1989 to 1990, it managed to pay homage to a classic that defined an era while also spotlighting its relevance to today.

- The Mountaintop (Front Porch Arts Collective)

Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Hall spun his magic, culminating in a monologue set against a rapid montage of people, movements and events from 1968 to 2024. The effect was as spellbinding as the magical 90 minutes we just spent in the presence of greatness, from the acting, writing, and direction to witnessing the final hours in the life of a man whose legacy is deservedly legendary.

300 Paintings (A.R.T.)

In 2021, Aussie comedian Sam Kissajukian quit stand-up, rented an abandoned cake factory, and became a painter. Over the course of what turned out to be a six-month manic episode, he created three hundred large-scale paintings, documenting his mental state through the process. His Drama Desk Award-nominated solo performance brought the audience on an original and poignant ride exposing his most intimate moments. The opportunity to graze among the real art was after show icing on a delicious cake.

Runners Up:

- Is This A Room (Apollinaire Theater Company)

A stunning production based on the F.B.I. interrogation of whistleblower Reality Winner.

2. The 4th Witch (Manual Cinema)

Hands down, the most wildly exciting and inventive production of the year. Manual Cinema pulled out all the stops, with shadow puppetry, live music, and actors in silhouette who redefined and reimagined theater. Inspired by Shakespeare’s Macbeth, a girl escapes the ravages of war and flees into the dark forest where she is rescued by a witch who adopts her as an apprentice. As she becomes more skilled in witchcraft, her grief and rage draw her into a nightmarish quest for vengeance against the warlord who killed her parents: Macbeth. Timely, relevant, and edge-of-your-seat engaging.

3. Sweeney Claus (Gold Dust Orphans)

Ryan Landry’s brilliant, irreverent, laugh-out-loud mash-up of Sweeney Todd and reindeer-randy Santa Claus brought camp to a new level. Terrific talent, costumes and choreography.

4. My Dinner with André (Harbor Stage Company)

A corner booth, fancy fare and tasty conversation — who doesn’t remember the cult frenzy caused by Louis Malle’s 1981 110-minute film that enchanted audiences, defied pigeon-holing and raised the bar on the “art” referred to as conversation? For those who found the film charmingly quirky, the splendid production at BCA Plaza Black Box Theatre was right up your alley.

5. The Piano Lesson (Actors’ Shakespeare Project)

Only stiff competition and the shadow of the high bar set by Seven Guitars in 2023 prevented ASP’s excellent production of Wilson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning drama from being among this year’s top ten.