Photos by Ken Yotsukura

By Shelley A. Sackett

Playwright Mfoniso Udofia’s nine-play Ufot Family Cycle follows the various members of the Nigerian Ufot family across three generations, starting with the brutal Nigerian Civil War (also known as the Biafran War) of 1967-1970. With the world premiere of The Ceremony, the sixth in the series, Udofia brings the family firmly into the present (2023) with all its contemporary social mores and cultural pressures.

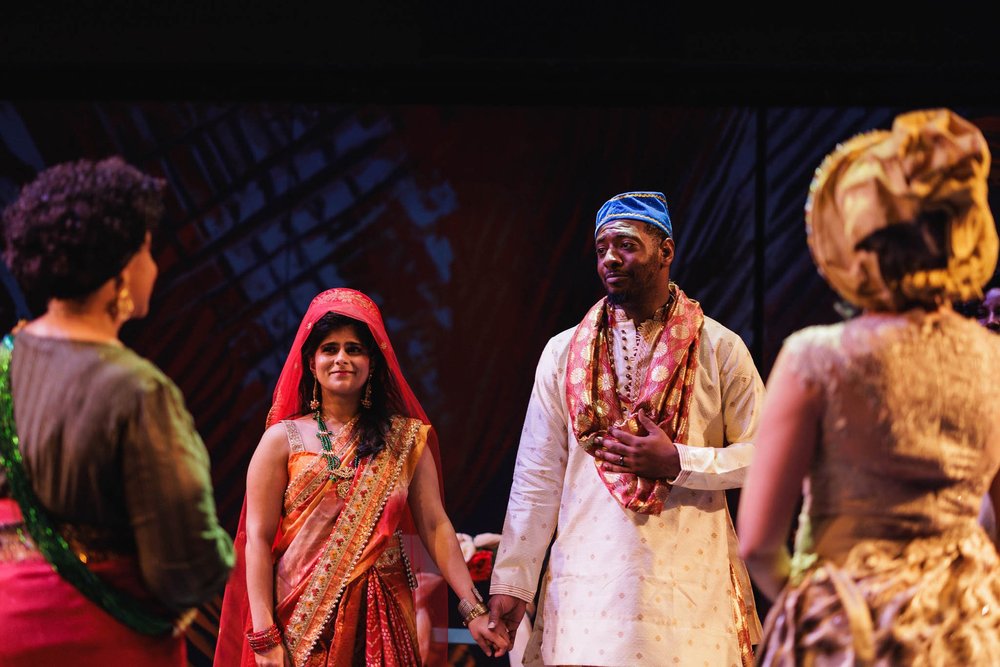

The Ufot Family Cycle is an unprecedented two-year city-wide festival where theaters and arts organizations around Greater Boston join to produce the nine plays in partnership with universities, social organizations, non-profits, and a host of community activation partners. The Ceremony is produced by the pay-as-you-are CHUANG Stage. At two plus hours (one intermission), the play focuses on the marriage between 31-year-old Nigerian-American Ekong Ufot (a fine Kadahj Bennett) and 32-year-old Lumanti Shrestha (equally fine Mahima Saigal), a Nepalese-American. Both are first-generation Americans, born in one country and raised by parents anchored in another

Whether the two can intertwine their Nigerian and Nepali heritages, with their different cultural traditions— and, more importantly, whether their families will let them — is the challenge they face as they try to plan a wedding that offends none and pleases most.

Compromise is the goal, but first the affianced couple must circumvent complex family issues, including their equally estranged fathers: Disciple (a powerful and complex Adrian Roberts), Ekong’s father; and Lumanti’s never seen but equally resistant father. How well they circumvent these stealth emotional and psychological IEDs will determine if Ekong and Lumanti make it to the wedding finish line.

Udofia leaves us guessing whether the couple can pull it off until the end, one reason the lengthy play doesn’t feel quite as long as it is.

[Although the nine plays are touted as being discrete stories linked together through lineage and characters, those unfamiliar with the Ufot family history may want to prepare by investing the time to listen to the excellent podcast, runboyrun. (It’s worth it for context). The third play in The Ufot Family Cycle, it focuses on Disciple as a boy in war-torn Nigeria and helps understand his tormented character, his relationship with his ex-wife and Ekong’s mother, Abasiama (the always welcome Cheryl D. Singleton), and the significance of such seemingly innocent props as a clock and a stick in The Ceremony.]

The play opens in Worcester in media res, with Lumanti center stage and the Nigerian women (Ekong’s mother, Abasiama, and sisters, Adiana (Regine Vital) and Toyoima (Natalie Jacobs)) above, on a lightly propped catwalk. Large staircases bookend the stage and are used with a practiced light touch under the spot on direction by Kevin R. Free. Cristina Todesco’s efficient and creative set and Andrea Sala’s restrained but effective lighting create a trifecta of simultaneous activity.

All the women are talking at once. Lumanti speaks into her cell phone in Nepali. Unlike some of Udofia’s previous plays (especially The Grove), the use of long passages of unsubtitled, non-English language is not off-putting. Here, the actors and Udofia offer enough clues so that the audience, instead of being shut out, is treated like special guests, invited for a behind-the-scenes peek at what life is like for this young, second-generation couple.

Lumanti is talking to her father, and we get the gist that she is getting an earful. Upstairs, the Nigerian women, with Abasiama lapsing into her native Ibibio, seem to be okay with the wedding, although the sisters are a little less enthusiastic than their mother.

It seems that white, in Nepalese culture, represents death, yet Lumanti has agreed to wear white for the wedding. “We wanted a western wedding,” she unconvincingly says.

The action swings back to the lower stage, where a table and couch shift the scene to Ekong and Lumanti’s apartment. Ekong is in the midst of a disciplined workout. His eyes are glued to one of three overhead projections showing the same episode of “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air,” the 1992 iconic Black American television show starring Will Smith (projection and digital content design by Michi Zaya).

Ekong doesn’t just enjoy the show, however. He needs it, and his eyes bulge with the panic of an addict who needs his fix until the set flips on. Only then can he truly relax. His mouth goes lax and he zones out from his outside world to the interior existence he channels, where he can step into a world of what his life could have been like if he had had different parents.

He sets a romantic table, complete with flowers and wine. When Lumanti enters the apartment, he is blindsided when she tells him her father, who had adamantly opposed and boycotted their wedding, has changed his mind. He will make the trip from Kathmandu after all. She is overjoyed.

“And you believe him?” Ekong asks. Ekong had assumed that, because Lumanti’s father was a no-show, his own father’s (Disciple) absence wouldn’t be questioned. Suddenly, Lumanti believes both their fathers are capable of change and she wants him to reach out again to his father with the news that hers will be in attendance.

It turns out Ekong never even spoke to his father. Lumanti, changed by the fact that her father will bear witness to the ceremony, has other news — she wants their wedding to be more traditional and include rituals from their two cultures.

“Why?” Ekong asks. “I’m Nepalese,” she replies. “Since when?” he demands. “Since dad said he’s coming,” she responds in all honesty.

And so the scene is set that will drive the rest of this thought-provoking, entertaining, and well-produced drama.

Udofia weaves together several subplots that show, rather than tell, the backstory of Ekong and his father’s 20-year estrangement. The owner of a successful physical therapy practice, Ekong bonds with Philip (the excellent Roberts), a client whom he equates with the idealized Black father figure in the TV show. He even tries to enlist him as a surrogate father, but Philip wisely declines.

Meanwhile, Lumanti navigates her own journey with her mother, Laxima ‘Amma’ Shrestha (Salma Qamain), and Auntie (Natalya Rathnam, funny and wise), and their reactions to the news that her father will attend. The older matriarchs share relationship and marriage advice and the three dig into the work of turning the secular wedding into more of a cultural celebration.

Act II brings out the dramatic strengths of the action and script, especially the scenes between Disciple, Abasiama and Ekong, and, of course, the wedding ceremony itself. Director Free makes free use of the full stage with multiple, simultaneous locations and conversations that keep up the pace and audience’s interest.

Eventually (no spoiler here-), the wedding takes place and the audience is both invited and delighted by the multi-traditional festivity. Something new and unique to Lumanti and Ekong (and their families) has been born from the blending of two families intent on preserving their heritage while acknowledging contemporary realities. Two parts really can make a new whole, but for the audience, the destination was never the brass ring. The journey, with all its potential derailings lying in wait and complicated intra-familial, was always what it was about.

Director Free brings out the best in his cast (with special shout-outs to Bennett (Ekong), Saigal (Lumanti), and Roberts (Disciple)), and Udofia’s script is crisp and unpreachy with just the right amount of humor and pathos. As an added bonus (like we needed one), we get to ride shotgun as both Ibibio and Nepali wedding traditions are unveiled before our eyes, a lovely touch.

There is a reason the show sold out almost immediately, although last-minute seats may be available. Do yourself a favor and try to be one of the lucky ones who scores one.

‘The Ceremony’ — Written by Mfoniso Udofia. Directed by Kevin R. Free. Presented by CHUANG Stage at Boston University’s Joan & Edgar Booth Theatre, 820 Commonwealth Ave., Boston through October 5.

For more information, visit https://www.chuangstage.org/the-ceremony