‘Touching the Void’ — Based on the book by Joe Simpson. Adapted by David Greig. Directed by Danielle Fauteux Jacques. Scenic and Sound Design by Joseph Lark-Riley; Lighting Design by Danielle Fauteux Jacques; Movement Choreography by Audrey Johnson. Presented by Apollinaire Theatre Company at Chelsea Theatre Works, 189 Winnisimmet St., Chelsea, through May 19.

By Shelley A. Sackett

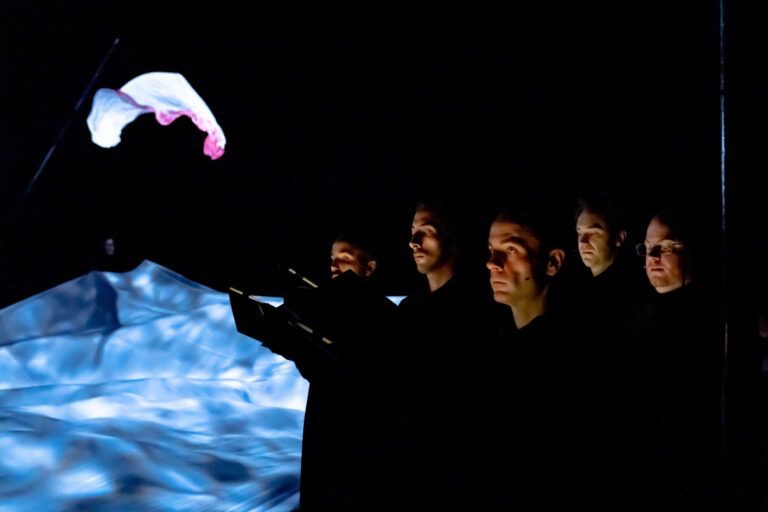

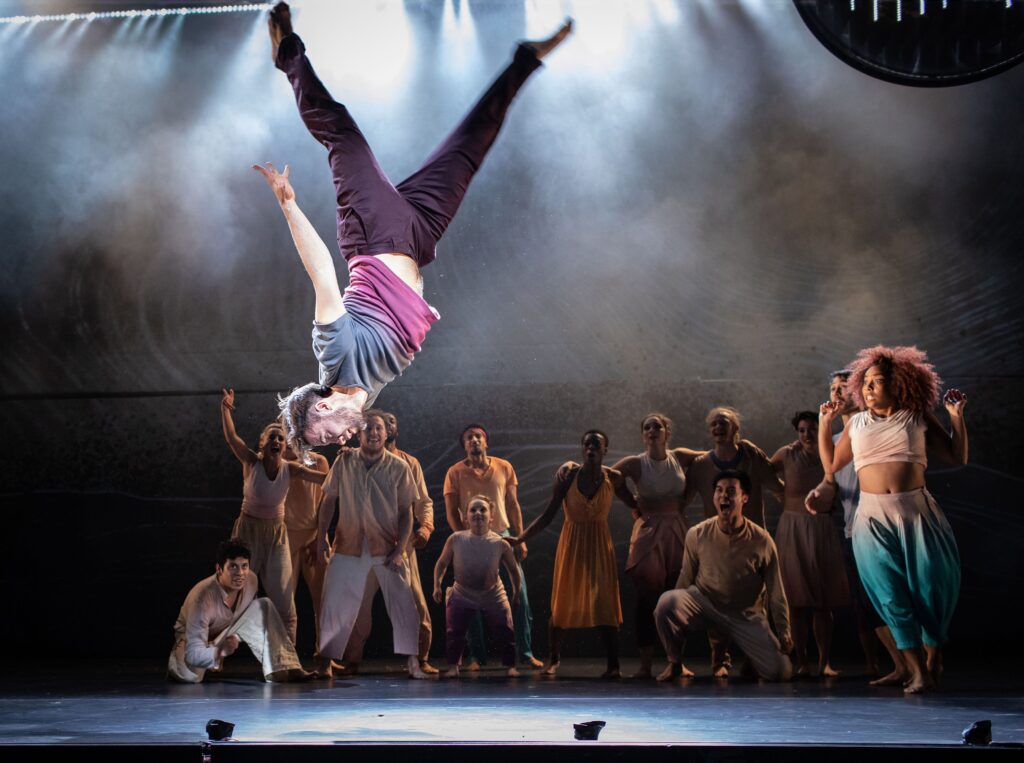

Touching the Void is special on so many levels. Presented in the intimate Chelsea Theatre Works theater, director Danielle Fauteux Jacques has done a brilliant job of creating multiple settings (including the side of a mountain in the Peruvian Andes!) with minimal fuss and to maximum effect. The four actors (Patrick O’Konis as Joe, Kody Grassett as Simon, Zach Fuller as Richard, and Parker Jennings as Sarah) are equally stellar, and David Grieg’s script is meaty and engaging.

The real star of the play, and an unfortunate rarity these days, is the plot-driven narrative. It is based on climber Joe Simpson’s memoir of his near-death climbing experience, a thrilling and engaging story. There is even a surprise twist ending, which Jacques reveals in a deliciously sly and clever fashion after the curtain falls when the audience least expects it.

Even before the play officially starts, the mood is set. A blond, sullen woman, clad in a leather jacket and boots strolls onto the stage. Her mouth is down-turned. She holds an unlit cigarette, sits alone at a booth in a casual pub, gets up to put a song on the jukebox, and sits down again. She nods, looks at the table, and sighs.

Jennings is captivating; it’s not easy to stay in character in a vacuum. The effect, thanks also to Jacques’ spot-on lighting, is like a Hopper painting come to life.

We learn she is Sarah, Joe’s sister. Joe, we also learn, is presumed dead. She has just come from his body-less wake.

Enter Simon, who survived the climb, and Richard, the base camp manager. She insists on hearing the entire story of the climb, from its planning phase in this very “climbers’ pub” to the moment when Simon cut Joe loose, leaving him to perish in a crevasse.

She wants to understand what drew her brother to take such a risk. She has to experience the climb as he did to do that because she doesn’t believe he is really dead.

Simon and Richard agree to relive the journey with her, and their story, relayed through Sarah’s non-climber eyes, is an enormous one, packed with insight, triumph and peril. It’s also a golden opportunity for director Jacques and sound designer Joseph Lark-Riley to strut their stuff by turning the small stage from the pub to an Andean peak — complete with crunching snow and howling winds that whip the climbers like flags— and back to the pub again.

We witness all this in hindsight and by the end, we share Sarah’s doubt about whether Joe really perished. (No spoilers, but the answer awaits over snacks and drinks in the lobby).

Simon accommodates Sarah’s need to know how her brother lived, not just how he died. He shows her how to climb, painstakingly using chairs and tipped tables to improvise the feeling and rush of the climb. Only after she can relate on a visceral level does the storytelling begin.

Back in 1985, Simon and Joe were experienced Alps climbing buddies who wanted to be the first to climb the West Face of the Andean Siula Grande mountain. Alpine style, which means without extra gear or yuppie brand name accoutrements. “Two men, a rope and the abyss. It’s beautiful, but it’s dangerous,” Joe explains.

Accompanied to base camp by their site manager, the amusing and irritating navel-gazer, Richard, the two set off on their impossibly low-tech journey. They make it up, but on the descent, Joe shatters his leg and then disappears over a cliff. With rescue an impossibility and faced with freezing winds and certain death if he didn’t immediately begin his own descent, Simon makes a gut-wrenching decision. Act I ends with him cutting the rope that tethers him to his partner.

Act II opens with Joe, alive, incredulously realizing his situation. He is as devastated by his physical problems of having a shattered leg and being at the bottom of a snow abyss as he is psychologically by the reality that his partner cut him loose to save himself.

Suddenly, Sarah is by his side, coaxing him on, helping him inch his way out of this Dante’s frozen circle of hell. Is Joe hallucinating? Is Sarah imagining herself by her brother’s side? While the agony of Joe’s navigating his slow descent sometimes feels tedious and overdrawn, trust me — it will all make sense in the end.

Touching the Void is an abundance of theatrical pleasures, most notably the performances by the four actors. As Joe and Sarah, Jennings and O’Konis are simply perfect. Fuller imbues Richard with just the right balance of goofiness and competence, and Grassett brings an arm’s length sang froid to Simon that leaves us guessing whether there might not be a few nefarious skeletons in his closet.

If you enjoy theater that makes you think and inspires post-show conversation and debate, then this play is a must. Besides marveling at an inspiring production, you are guaranteed to leave wondering how this story could possibly be true.

For more information, visit apollinairetheatre.com