Pink brings out the worst in me. I chafe and cringe, feeling trapped in a sorority I never pledged. Blame it on my vestigial 60’s feminism, or the resentment I still harbor over the pink butterflies wallpapered to my bedroom ceiling without my knowledge or consent when I was seven. Whatever. Just bring me pink as undiluted red.

My spousal equivalent, on the other hand, is as keen on pink as I am not, especially when it comes to flowers. Only recently he finally gave up the challenge of changing my mind with a bouquet of the right shade of pink. He, like me, was convinced that it simply didn’t exist.

Until, that is, the MFA’s gender- bending “Think Pink,” an exhibit devoted to exploring design and gender with a wide range of all things pink from the 17th century to today.

The compact but sprightly show traces the evolution of pink with clothing, jewelry, accessories, graphic illustrations and paintings drawn from the museum’s collections. The fashions are stunning, with examples from Christian Dior, Elsa Schiaparelli, Ralph Lauren and Oscar de la Renta. The hats, in particular, are whimsical and striking.

We learn that both males and females claimed pink as their own, until the 19th century when men started wearing dark business suits and pink took on a feminine identity. Over the centuries, cultural, artistic and technological changes have swung the pink pendulum from rose to magenta to shocking pink and back again. Artificial dyes inspired neon, nervy, shocking pink, a color sometimes surrealist in application. Since 1992, pink has come to symbolize the global effort to fight breast cancer, thanks to the efforts of Estee Lauder and former SELF Magazine editor Alexandra Penney.

Woman’s hat Flo-Raye, New York 1945–55 Plaited straw and artificial flowers * Gift from the Collection of Violet Manno Shumsky through her estate

Woman’s hat Flo-Raye, New York 1945–55 Plaited straw and artificial flowers * Gift from the Collection of Violet Manno Shumsky through her estate

Amidst the yards of charmeuse, feathers and sequins, the most eye-catching is a sleek, pink, wool twill man’s suit, designed in 2013 by Ralph Lauren for Vogue International editor-at-large, Hamish Bowles. The ensemble is intended to copy Robert Redford’s costume from the 1974 film version of “The Great Gatsby.” It would look great on David Bowie, too.

Another standout is Kenneth Paul Bock’s “Model in Sweeping Pink Coat,” a watercolor illustration for an Oscar de la Renta W Magazine design.

Female model in sweeping pink coat by Kenneth Paul Block (American, 1925– 2009)1980sWatercolor and black marker on paper * Gift of Kenneth Paul Block, made possible with the generous assistance of Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf

Female model in sweeping pink coat by Kenneth Paul Block (American, 1925– 2009)1980sWatercolor and black marker on paper * Gift of Kenneth Paul Block, made possible with the generous assistance of Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf

“Think Pink” is informative, thought-provoking and for some, transformative. As society embraces more fluid ideas of gender and color, perhaps it is time for this stubborn holdout to do the same.

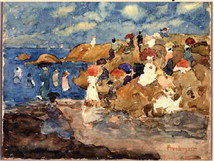

Revere Beach 1896.

Revere Beach 1896.