By Shelley A. Sackett

It’s easy to understand why George Balanchine’s Jewels has endured for more than 50 years. An abstract work, the triptych is not shackled to the narrative constraints of traditional ballet. Rather, each of its three pieces — “Emeralds,” “Rubies,” and “Diamonds” — is a pure sensorial feast of luscious music and stunning choreography. The work is easily appreciated by audiences new to the genre, yet also presents challenges for experienced dancers and critical aficionados.

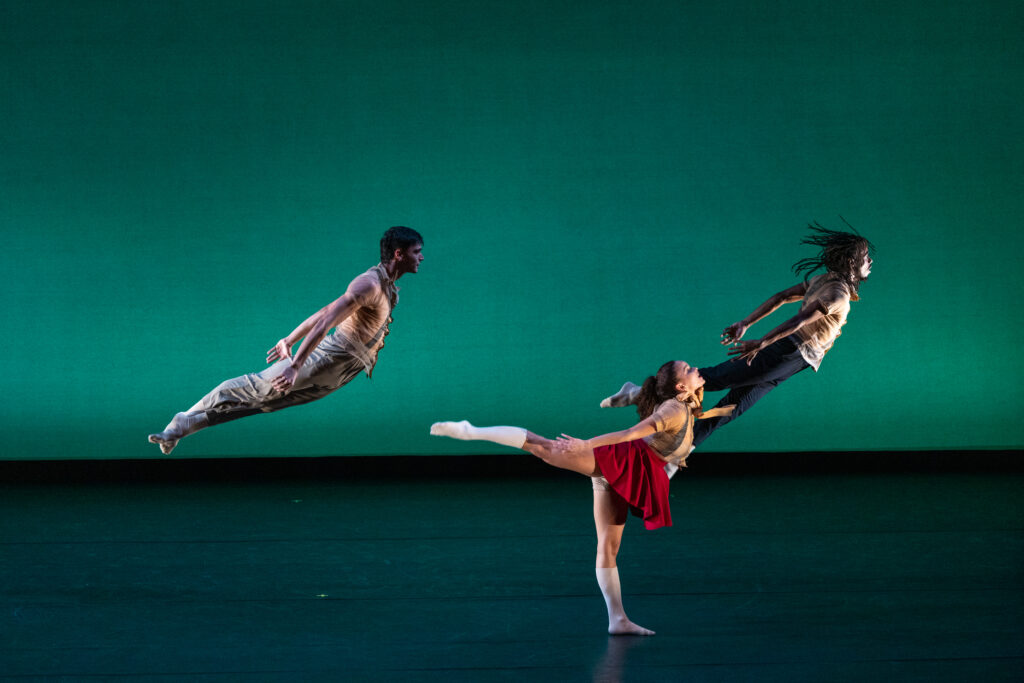

The first Friday evening performance opened with the dreamy and poetic “Emeralds.” Featuring “Pélléas et Mélisande” and “Shylock” by the French composer, Gabriel Fauré, the piece is meant to evoke Paris. The curtain raised on ten members of the corps, bejeweled in crowns and regal necklaces and dressed in a lime green chiffon that you could almost taste. Like porcelain figures in a French masterpiece oil painting, the figures seem momentarily frozen, and then suddenly the stillness is broken and the dancers spring to life.

With its green backdrop and even greener costumes, “Emeralds” evokes the pastoral enchantment of forests, hunting scenes, courtships, and a tapestry of youthful magic. Balanchine mixes it up enough to keep the audience engaged (pas de deux, staccato hand movements and playful, joyful solos) without demanding overthinking. Oboes, French horns, and flutes present the perfect shading for the elegant partnering of standouts Lia Cirio and Patrick Yocum and the perfect lush background for the final piece, where the full corps strikes a tableau that mirrors and bookends the piece’s opening scene.

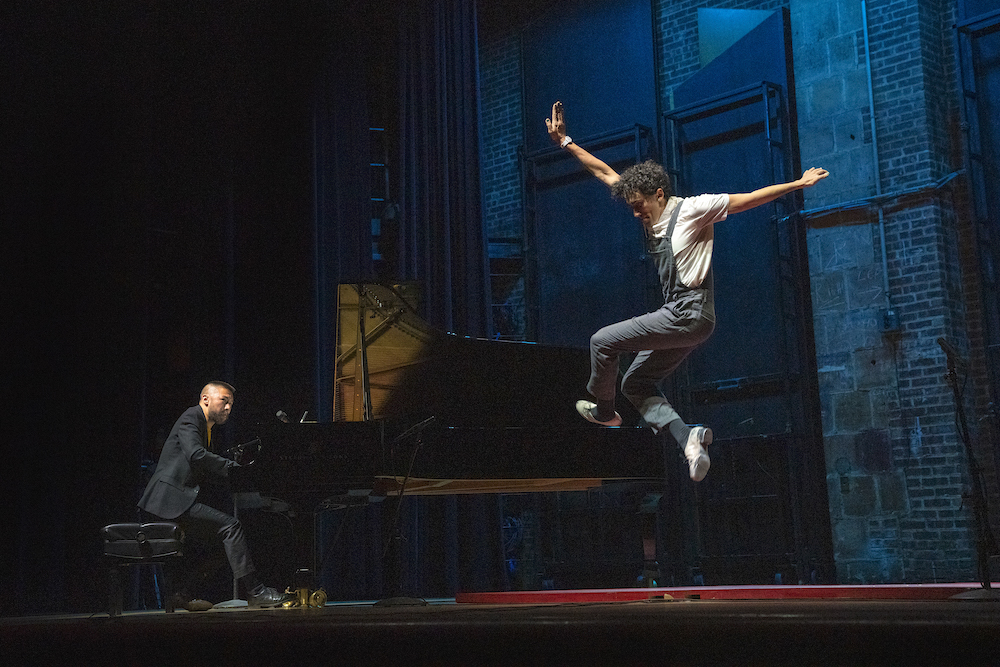

After a 20-minute intermission (the show runs 2 hours, 10 minutes total), the evening shifts gears with “Rubies,” Balanchine’s jazzy, modern and saucy piece set to Stravinsky’s “Capriccio for Piano and Orchestra.” Witty, playful and athletic, the dancers emote and engage with the audience, winking, nodding and sharing a sly smile. Karinska’s flapper-inspired ruby red costumes are perfect companions.

Balanchine clearly wanted everyone to have fun with this bold, American neoclassical piece. Influenced by Broadway and sexually charged, its emphasis on communication and merriment contrasts sharply with the preceding arms-length, performative “Emeralds.” The dancers jump rope, ride stick ponies and flirt shamelessly. Chyrstyn Mariah Fentroy is a cheeky breath of fresh air and Chisako Oga and Sun Woo Lee are evanescent as a seductive Adam and Eve couple who tango their way (among other feats) through Ruoting Li’s brilliant rendition of Stravinsky’s piano solo.

Balanchine circles back to his Russian roots with “Diamonds,” set in St. Petersburg to Tchaikovsky’s “Symphony No. 3, Op. 29, D major.” A tribute to Russian classicism, costumes are glittering white tutus and the set includes a glistening chandelier and generous pleated layers of thick satin draped and tiered along the stage’s sides and across the front. The effect is of an ice castle filled with sugar plum fairies until the dancers begin to prance like reindeer and engage in exuberant couplings.

Grand and imperial, the dancers exhibit disciplined symmetry, creating patterns and shapes. A pas de deux, long and undulating as it unfolds, features the marvelous Viktorina Kapitonova (and talented Sangmin Lee) who steal each other’s — and the audience’s — hearts as their movements reflect the music’s building crescendos and ascending scales, only to resolve harmonically and melodically. There is only grace and beauty in their dance, although the music could have been equally served by more urgent and fitful movements. Fortunately, Balanchine opted for the former approach.

Jewels premiered in 1967 at New York Ballet, where Balanchine was Ballet Master and Principal Choreographer. The full length ballet, one of the world’s first “abstract” ballets, was inspired by a visit to the renown jeweler, Van Cleef & Arpels. Struck by the shimmering contents of the store’s cases, he decided to create dances that would emulate those shimmers with distinctive moods, styles and musical voices.

Boston Ballet is off to a spectacular start in its 2025-2026 season. Be sure to visit their site for more information and to purchase tickets at https://www.bostonballet.org/

‘Jewels’ — Choreography by George Balanchine. Music by Gabriel Fauré, Igor Stravinsky, and Peter Tchaikovsky. Costumes by Karinska. Lighting by Brandon Stirling Baker. Presented by Boston Ballet. With the Boston Ballet Orchestra conducted by Mischa Santora. Run has ended.