‘The Moderate’ — written by Ken Urban. Direction and Multimedia Design by Jared Mezzocchi. Scenic Design by Sibyl Wickersheimer; Lighting Design by Kevin Fulton; Sound Design by Christian Frederickson; Assistant Projections Design by Emery Frost. A Catalyst Collaborative@MIT Production presented by Central Square Theater, 450 Mass. Ave, Cambridge through March 1.

By Shelley A. Sackett

The Moderate is not for everyone.

Kudos to Central Square Theater for its excellent job of warning that the play contains mature themes, including images, video, and audio depictions of violence, nudity, and racism. Its Content Transparency Statement goes even further, stating, “Central Square Theater cares about the well-being of our audience. We are committed to sharing information about stage effects, sensory experiences, and topics people may find distressing in advance of attending our productions.” The theater recommends that audience members be older than 17. (See full program here).

On a recent Sunday matinée, one woman left early, clearly distressed. The rest of the capacity crowd stayed put, transfixed by one of the most compelling productions to hit Boston this season.

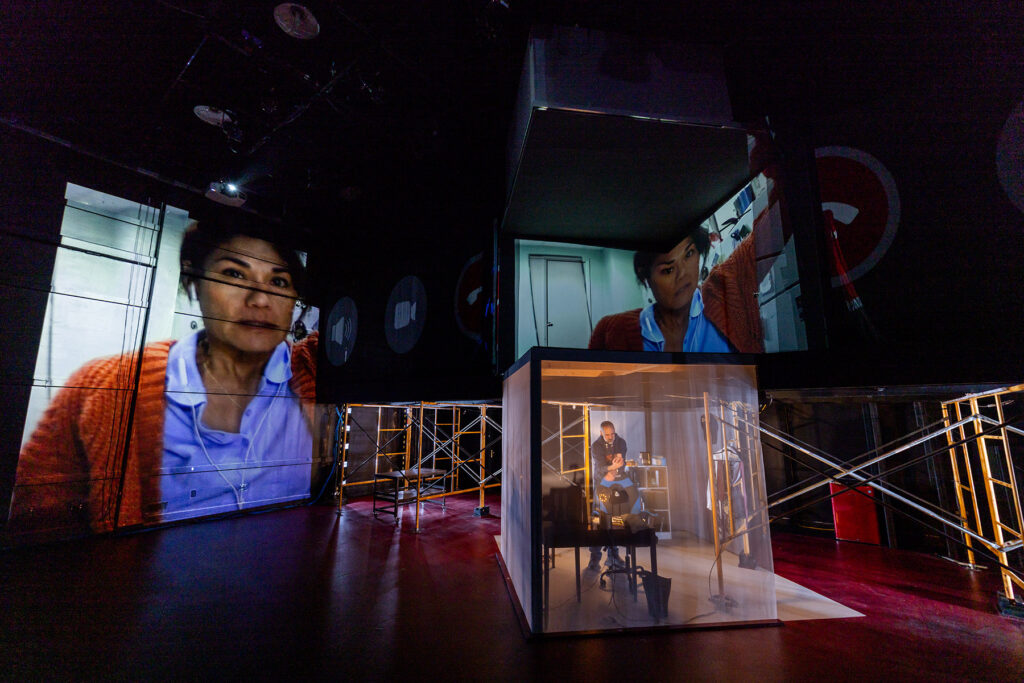

Two-time Obie Award winner, director and multimedia designer Jared Mazzocchi and scenic designer Sibyl Wickersheimer set the stage and mood before the play even begins. Stark metal scaffolding and 10 wrap-around screens hover above a screened gazebo. It is March 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic and lockdown. Inside the gazebo/cage, a man sits hunched over his computer, busy at work. His face is projected in double negatives above, framing shooting purple lights. Suddenly, the other screens come to life with images that range from loving couples holding hands to actual beheadings.

The man behind the screen is middle-aged Frank Bonner (the always excellent Nael Nacer), newly estranged from his wife, Edyth (Celeste Oliva), and his teenage son. He’s also just lost his job at Kohl’s and is facing mounting debt, including loans he took out to pursue a degree in English literature at a community college. Isolated and desperate, Frank has applied to be a content moderator for a company subcontracted to a company contracted by the social media global giant meant to be Facebook.

During his interview with Martin (Greg Maraio), Frank (and the audience) learn exactly what the job entails.

When viewers encounter content on the web they deem to be “questionable” and alert the provider, Martin explains, that content goes into a queue for human evaluation. The evaluator views the content and presses either “Accept” or “Reject.” Personal beliefs are irrelevant to the job, Martin advises (warns?) Frank. “Just follow the company guidelines.”

Martin also warns (advises?) Frank to “try to look but not see” some of the more traumatic images that will parade across his screen, especially anything having to do with ISIS.

Frantic for a job and any diversion during his marital and societal isolation, Frank jumps at the chance to earn $17 an hour.

As he screens a never-ending stream of debatable content, the work takes a predictable emotional and psychological toll, and the audience, riding shotgun as we are, channels that upheaval. A young but seasoned colleague, Rayne (the enormously appealing spitfire Jules Talbot), counsels Frank when he hears that he wants to help a kid named Gus (Sean Wendelken), who has repeatedly filmed and posted evidence of beatings by his father. His pleas for help have struck a long-buried chord in Frank.

This may also be an opportunity to use his job (and the Internet) to do some good. Redemption? Perhaps. Relief? Definitely.

Not so fast, Rayne cautions. Never, ever get personally involved. “This job changes you; you decide how. It can make you better, or it can break you,” says Rayne. “Compartmentalizing is the only way to survive.”

Frank struggles with more than whether to protect a stranger (and, perhaps, heal himself). Society’s obsession with technology and the power of those in charge of that technology literally shapes the world we live in. Are moderators defenders of decency and morality or simply “Internet garbage men” doing the bidding of corporate profit seekers and right-wing fanatics, as Rayne suggests? The answers are as slippery as the slope that forces Frank to “accept” a photo of a white family embracing a young black girl titled, “Every family needs a pet,” which, according to corporate guidelines, is only ambiguously racist.

Playwright Ken Urban interviewed scholars and people who worked as moderators to create his one-act drama. He envisioned an innovative staging that would incorporate live video in “surprising ways” while exposing audiences to the kind of disturbing visuals that cling to the underbelly of the dark web.

Mezzocchi and his team are more than up for the job. For this world premiere, they create a technological landscape that seamlessly invades body and mind, creating a secret world we all live in, where erasing a video does nothing to stop the underlying evil. When a technological glitch early in the 90-minute production brought the lights back up, it was as if the fourth wall melted.

Suddenly, we were all in it together, all hostage to the technology we can’t live with and can’t live without. As Nacer busied himself at his desk, the audience was in his shoes, wondering whether this was a staged or real hiccup, trying to figure out if it’s ok to busy ourselves too, and maybe even turn our phones on and cop a quick fix.

Lest the misimpression be left that The Moderate is a 90-minute, relentless parade of vile images, rest assured that Urban has created a multi-layered story with complex, multifaceted characters who lead complicated, messy, and real lives, peppered with real challenges. A universally talented cast, bang-up production, and sharp direction bring this very human story to life and force us to confront some uncomfortable but valid questions about whether we can control technology or whether our addiction has forced us to relinquish the driver’s seat. One thing is for sure — The Moderate is certain to spark lively post-theater discussions.

For more information, go to: https://www.centralsquaretheater.org/