Photos: Nile Scott Studios and Maggie Hall

By Shelley A. Sackett

Ayodele Casel’s ‘Diary of a Tap Dancer’ defies pigeonholing. First, it is a crackerjack tap dance concert, choreographed and performed by a jubilant devotée of the genre whose sensitivity to its rhythmic musicality keeps the action moving and the audience’s toes tapping along.

Second, it is a narrative documentary that “shines a light on women hoofers,” especially the unknown and forgotten black tap dancers of the 1920s through the ‘50s who blazed a trail for others, like Casel, to follow. Projection Designer Katherine Freer has curated a six-screen still and moving visual accompaniment that introduces us to all the dancers who might have been written out of history — women like Juanita Pitts, Jeni Le Gon, Cora LaRedd, Louise Madison and Marion Coles — but for her efforts to draw attention to them.

“I have an intense need, desire and responsibility to speak their names,” Casel, the self-proclaimed sepia Cinderella of tap, shares. “They were entrepreneurs, choreographers and dancers. Our time on earth matters. Don’t wait for an invitation to tell your story.”

Additionally, Casel’s ‘Diary of a Tap Dancer’ is just that- an oral diary that tells, in upbeat, humorous and, at times, painfully repetitive detail, the story of her life.

Born in the Bronx to a Puerto Rican mother and African American father (whom she didn’t meet until she was 17 years old), she was sent as a child to live with her Puerto Rican grandparents, where she honed her scrappy spirit by getting into fist fights with boys. When she returned to the Bronx, she and her mother watched old movies and read movie magazines, falling for the glamor and magic of Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire. She discovered the world of tap during a high school class in movie history. Later, as an NYU theater major, she took her first tap class, showing up with shoes from “Payless” that were as close to Rogers’ as she could find.

“Tap is magic,” Casel says. “It changed my life.”

Her single-minded persistence landed her a spot as the first woman in Savion Glover’s (of mid-90s off-Broadway hit, “Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk,” fame) dance company, a real turning point in her career. Tap legend Gregory Hines has referred to her as “one of the top young tap dancers in the world.”

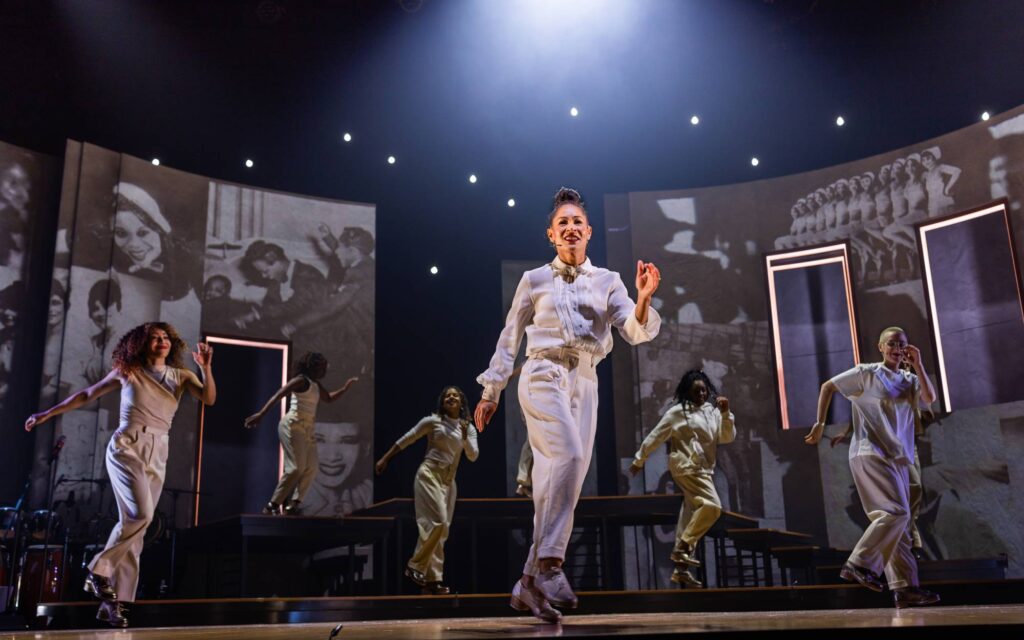

When it comes to paving the way for other marginalized dancers, Casel doesn’t just talk the talk; she also walks the walk (taps the tap?) by sharing the stage and spotlight with seven female and nonbinary young dancers who both complement each other as an ensemble and shine as soloists. But the spritely, charismatic, and extraordinarily talented Casel can’t help but steal every scene with the simplest flap-ball-change. Who knew tap could be so orchestral and communicative?

Under Torya Beard’s (Casel’s longtime collaborator and wife) direction, the atmosphere is set even before the show starts with an almost holy ambient organ major harmonic dyad punctuated by muted city traffic, sirens, and birds. A simple blue set sports what looks like graffiti but is actually a photograph of 18th-century legislation forbidding slaves from owning drums.

A slow spotlight reveals white-clad dancers using every inch of Tatiana Kahvegian’s sparse but effective stage. Dancers are scattered in little solo spaces reminiscent of the staging of “The Lion King.” When the soundtrack kicks in and they all start tapping, it’s like a magical sound bath of rhythm and movement.

Backed by a terrific trio of on-stage musicians (Carlos Cippelletti on piano, Raul Reyes Bueno on bass and Keisel Jiménez Leyva on drums), the musical dance numbers are a pure delight. Casel tells her intimate and powerful story through straight narration, rap, beat and counter-beat. Her acting chops show in the comfort with which she addresses the audience. It’s no surprise to learn that “Ayodele” is Yoruban for “joy.” Casel is not just a top-notch dancer and choreographer; she is genuinely warm, funny, smart, guileless, and humble. She is also an articulate, eloquent, and bold guide who unlocks the enchantment and triumph of the human spirit that is the essence of tap.

The problem (at least at last Sunday’s world premiere production, which ran 30 minutes beyond the show’s already overly generous 2 hours with one intermission) is that Casel has a lot to say about a lot of topics about which she is understandably passionate. “This show is narrative justice,” she explains.

But by trying to tackle such big-ticket items as racism, sexism, African American history, misogyny, and historical exclusion, instead of leaving her audience feeling enlightened and informed, she leaves them wishing for more dance and less talk. A LOT less talk.

While Casel is an excellent and engaging narrator, it is the magic language of her syncopated footwork and vocal scat work that offer a more compelling and emotionally accessible (and less preachy) tribute to the art form of tap and the black foremothers she seeks to honor. A little editing could go a long way.

‘Diary of a Tap Dancer’ – Written and Choreographed by Ayodele Casel. Directed by Torya Beard. Musical Direction by Nick Wilders; Scenic Design by Tatiana Kahvegian; Costume Design by Camilla Dely; Lighting Design by Brandon Stirling Baker; Sound Design by Sharath Patel; Projection Design by Katherine Freer; Compositions, Orchestrations, and Arrangements by Carlos Cippelletti, Ethan D. Packchar. Presented by American Repertory Theater at the Loeb Drama Center, 64 Brattle St., Cambridge, through January 4, 2025.

For tickets and information, go to: https://americanrepertorytheater.org/shows-events/diary-of-a-tap-dancer/