Photo: Nile Scott Studios

By Shelley A. Sackett

Karen MacDonald, recently introduced as “the empress of Boston,” adds another gem to her tiara with her portrayal of Prudence Payne, a Dorothy Parker-esque reviewer whose sharp wit, acid tongue and encyclopedic familiarity with minutiae of all things cultural have earned her many awards. We are introduced to her as she and her son, Thomas (De’Lon Grant) sit in the Brook Hollow clinic anteroom, awaiting a consultation with a doctor. The television is blaring pablum. Pru regally grabs the remote, waves it like a magic wand. She tries to turn the television set off, but can’t. She retakes her seat, slumping in confused defeat. Tommy reminds her that there are other people in the room who may want to continue watching. “Re. Member,” Pru says, enunciating each letter as if it were a syllable unto itself.

In a flash of a flashback, the music cues and we are transported to 1988 (kudos to Set Designers Christopher and Justin Swader, whose elegantly simple set easily morphs in our mind’s eye from medical waiting room to time travel “Beam Me Up Scotty” mode to grand ceremonial dais.) Pru is at the pinnacle of her career, about to become the first woman and first critic to receive the alliteratively laden AAAA’s (American Academy of Arts and Aesthetics) Abernathy Award.

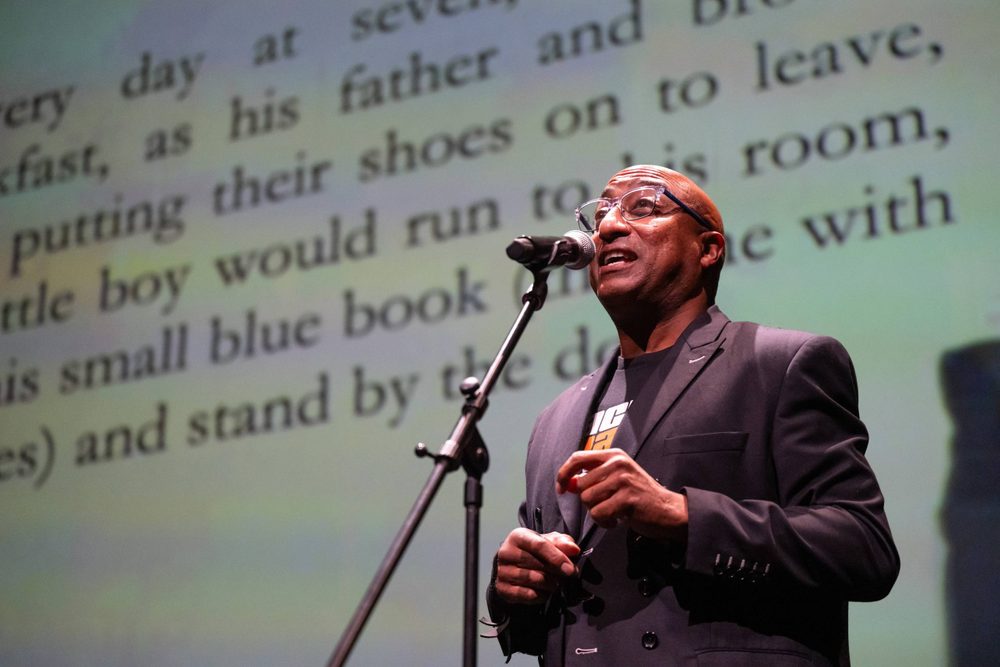

We catch her as she mounts the podium amidst resounding applause. Her acceptance speech is impudent, provocative and riotously funny. She is brilliant and revels in peppering her monologue with fast-paced literary citations that showcase her sophisticated and seasoned palette while challenging her audience to guess their source. If there were a Mensa Jeopardy, Pru would be its host.

But a sudden shift, almost imperceptible at first, indicates all is not quite right with Pru. She devolves into F-bombs, rectal references and borderline slander. Thomas approaches her, but she waves him away. When she loses her place and starts to panic on stage, MacDonald’s prodigious skills are on full display. In the blink of an eye, her Pru actually pales, her face sags, her shoulders droop and her speech falters. Thomas rescues her and escorts her to her seat. We are back in the waiting room, where the TV continues to blame.

Brook Hollow, it turns out, is a Massachusetts memory clinic where Thomas has brought Pru for evaluation following her speech and the uproar it causes. To smooth the turbulent wake Pru left with the AAAA, he has offered up her memoir as a peace offering, due the following fall. It is only two weeks later, yet we sense that Pru has deteriorated. She is still irreverent and acerbic, yet her confusion and slips are more frequent.

Thomas is desperate to thwart his mother’s memory loss. It is an irony lost to no one that a woman whose memory is galloping away is chasing her past before it is out of reach in order to write her memoir.

For the next 90 intermission-less minutes, we ride shotgun over two decades as Pru travels down the path of full-blown, irreversible dementia. If this sounds gut-wrenching and jarring, it is. Yet, in the skilled hands of master wordsmith and award-winning playwright Steven Drukman (and under Paul Daigneault’s flawless and sensitive direction), it is also rip-roaringly funny and brimming with empathy. The Newton native has married head and heart in a tightly crafted script that abounds in clever one-liners and zinger plays on words. (It also has tons of fun local references). Painful as the topic and Pru’s story are, Drukman’s humor and hopefulness dull the knife’s sharp blade just enough to prevent the play from circling the drain of utter despair.

He has also penned a group of supporting characters who each have independent agendas and stories, yet who interlace as an ensemble that embraces and supports the play’s eponymous Pru.

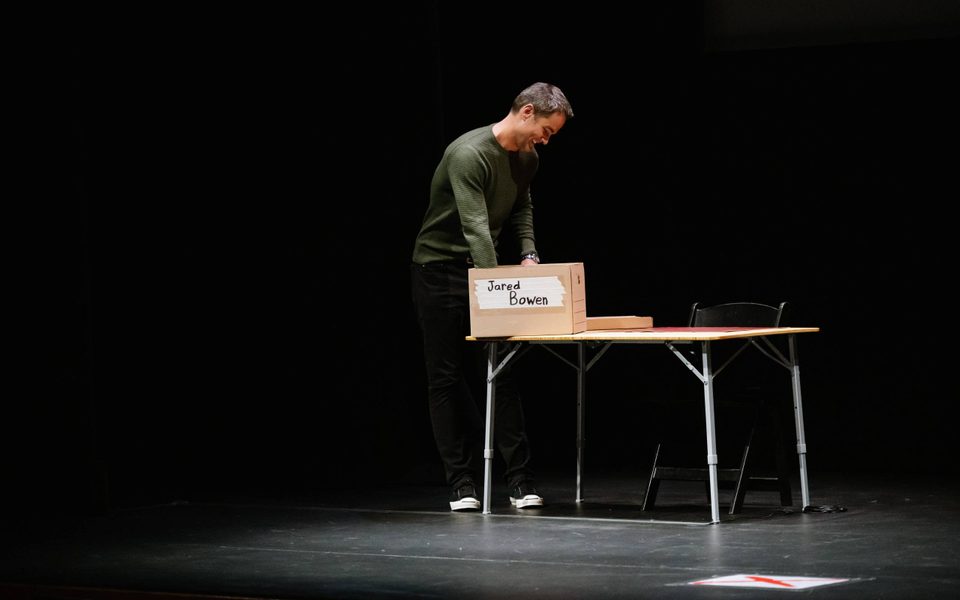

Pru and Thomas, an aspiring novelist, meet with Dr. Dolan (the magnificent Marianna Bassham in an unfortunately understated, somewhat unimaginative role), who, unsurprisingly, wants to admit Pru for observation. They start to protest when Pru spots Gus Cadahy (the quietly show-stopping Emmy, SAG and IRNE Awards winner Gordon Clapp), a custodial engineer who is accompanied by his son, Art (Greg Maraio). They, too, are at Brook Hollow so Gus can be evaluated for memory decline and associated behaviors.

Pru and Gus are yin and yang, opposite forces that form a whole in a balance that is always changing. He is lower middle class, uneducated, and speaks with a thick Boston accent. She is stratospherically wealthy, wears her pedigree on her sleeve, and effects a Brahmin patois. He is unapologetic, hilarious and down to earth, determined to squeeze every last drop of fun and pleasure out of life. He makes no excuses and accepts what comes his way.

She is calculated, driven and controlling. “Good enough” are two words meant to be spat, like a curse. Despite her sophistication and breeding, she is far crasser than the social mores minded Gus.

Their love affair at Brook Hollow opens the door to more than a delineation of their differences. Pru is Gus’ missing piece and vice versa. He softens and grounds her, whether playing gin, dancing, making love or reeling her back from memory’s steep precipice. Pru, for the first time in her life, is able to let go, let loose and let herself love and be loved.

Meanwhile, their sons have their own backstory, which would be a spoiler to divulge other than to let slip that, while their parents are creating new memories, their sons are revisiting old ones.

Boston native Maraio is terrific as Art, both in his interactions with his father and with Thomas, especially as concerns their parents’ relationship. He brings a nuanced vulnerability to his external impermeability. Grant, so wonderful as Keith in “A Case for the Existence of God,” brings that same sweet openness to Thomas, a quiet defenselessness and optimism.

Although Drukman meanders peripherally into timely topics of the 1990s and 2000s (AIDS, politics, and the demise of cultural standards, for example), he has the good sense to use this detour for context rather than theme. He has written an important and riveting play about a timely and difficult subject that is, in its own right, much more than just “good enough.”

We ache for Pru and her family, but covet our view through the keyhole at that in-between stage where one starts to become unglued. yet is still together enough to be aware of what is happening (and what is to come). We also come face to face with some heady and introspective queries.

How, for example, do you sum up a person, especially one whose life ends in the black hole of dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease? Who is the real Pru? How should she be remembered? Is it fair to her to remember her in her absolute decline or is it dishonest to remember her otherwise? Do we curate our own memories? Do others curate theirs of us? At the end of the day, does it really matter?

As her own memories dissolve and past human connections along with them, Pru has moments lucid enough to still contemplate Pru-worthy big picture questions. What if, she wonders, her entire life was just a memory trick?

What if, indeed.

“Pru Payne”— Written by Steven Drukman. Directed by Paul Daugneault. Presented by SpeakEasy Stage at Boston Center for the Arts, Calderwood Pavillion, 539 Tremont St., Boston, through Nov. 16.For tickets and more information, go to https://speakeasystage.com/