By Shelley A. Sackett

Every family has that iconic favorite movie or television show that follows its members throughout childhood, adulthood and parent/grandparent-hood. For mine, it was (and is) “Mrs. Doubtfire,” the 1993 movie that has been with us from Blockbuster rental to VHS to DVD to stream-on-demand. So any live version of this holy grail was going to have a very high bar.

Thankfully, Broadway in Boston and Work Light Production’s musical version of the Broadway hit at the Emerson Colonial Theatre manages to hurdle over that bar more often than knock it over.

Thanks to (some) stand-out acting, strong vocals and lyrics that move the narrative along and give insight into the characters, Mrs. Doubtfire is easy to recommend to even the most die-hard Robin Williams/Harvey Fierstein/Sally Field/Pierce Brosnan fans.

When it falls down, however, it crashes. The choreography drags just often enough and the set designs feel flimsy and lazy (mostly painted backdrop screens). The biggest transgression is Mrs. Doubtfire’s mask, which looks like a combination of Lurch’s waxy forehead and a cross between Howdy Doody’s and Hannibal Lecter’s jaw. Heartbreakingly distracting, it is a constant reminder of why the original film remains safely inimitable.

Nonetheless, the production was fun and fast-paced. The story, for the uninitiated, revolves around Daniel’s efforts to maintain contact with his three kids after a messy divorce from his wife, Miranda. An out-of-work freelance voice actor, Daniel is a loving and devoted father to his three children: 14-year-old Lydia (a show-stopping Alanis Sophia), 12-year-old Chris (Theodore Lowenstein on Wednesday evening), and five-year-old Natalie (Ava Rose Doty). However, his hardworking wife Miranda considers him immature and unreliable.

After quitting a gig following a disagreement over a morally questionable script, Daniel throws Chris a chaotic birthday party, despite Miranda’s objections due to Chris’s poor grades. In the ensuing argument, Miranda says that she wants a divorce. Due to Daniel’s unemployed and homeless status, Miranda is granted sole custody of the children, with Daniel having visitation rights every Saturday; shared custody is contingent on Daniel finding a steady job and suitable residence within the next three months.

In the meantime, he will be under the watchful eye of Wanda Sellner (a marvelous Kennedy V. Jackson), his court-appointed social worker.

He rents a shabby apartment and takes a part-time job as a janitor at a television station. After learning that Miranda seeks a housekeeper, Daniel secretly calls her using his voice acting skills to pose as various undesirable applicants before calling as “Euphegenia Doubtfire,” an elderly Scottish nanny with strong credentials. Impressed, Miranda invites Mrs. Doubtfire for an interview. Daniel’s brother, Frank, a makeup artist, and Frank’s husband, André, help Daniel appear as an old lady through the use of makeup and prosthetics. (Enter the unfortunate mask…)

As Mrs. Doubtfire, Daniel excels at parenting, becoming the kind of father he couldn’t be before. The comedy ensues as he attempts to balance his life as Daniel and as Mrs. Doubtfire, particularly when he is on the cusp of landing a terrific new job as the creator/star of a children’s television show and Miranda’s new boyfriend, Stuart Dunmire, becomes a threat as a potential father figure.

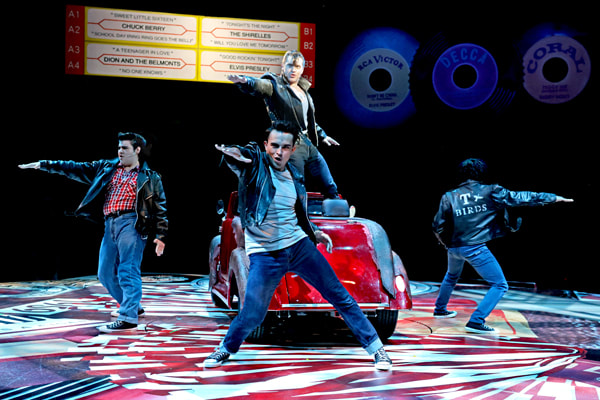

We are introduced to Daniel (an enjoyably manic Craig Allen Smith) in the opening number, “That’s Daniel,” where his Peter Pan, slapstick, playful qualities are on full display. “You think you’re being amusing, but you’re just annoying,” his director tells him moments before firing him. The entire cast, and especially wife Miranda (Melissa Campbell, a terrific singer) wholeheartedly agree.

The makeover scenes are hilarious and DeVon Wycovia Buchanan, as André, is a real scene stealer. Having Frank (Brian Kalinowski) yell every time he lies is a cute conceit at first, but ends up hamstringing the actor and turning his character into more of a cardboard, two-dimensional role.

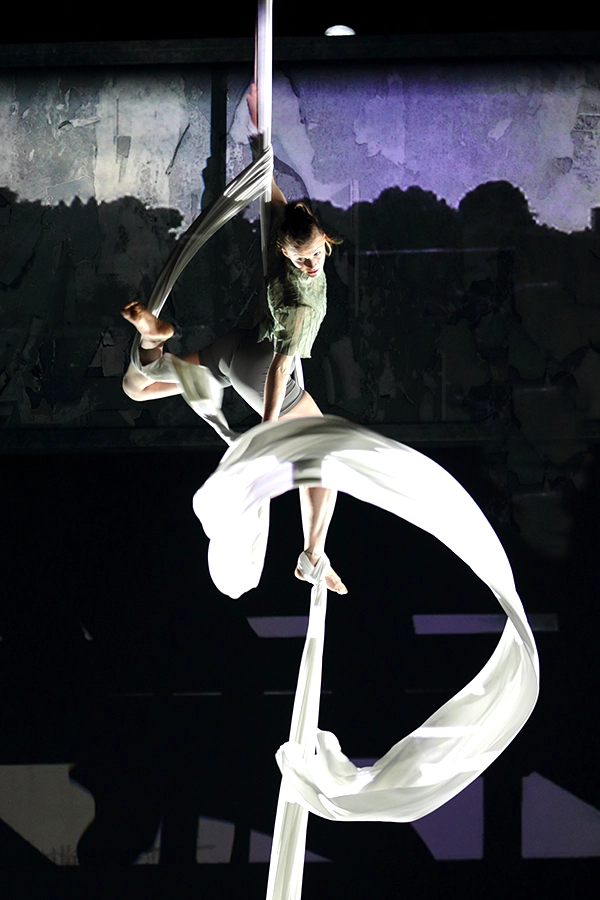

“Easy Peasy,” featuring Mrs. Doubtfire and the entire ensemble, is one of the musical’s most enjoyable. A chorus of tapdancing chefs (Kristin Angelina Henry is a standout) help the lyrical narrative move along, and the famous vacuuming scene (“I’m Rockin’ Now”) will please even the pickiest Robin Williams fan. As Daniel/Mrs. Doubtfire takes his parenting seriously and bonds with his kids in more mature and parental ways, their interactions take on a poignancy that even transcends the distraction of his mood-disrupting mask.

As the plot moves along, it also thickens. Act II brings Daniel’s unmasking (alas, figuratively only) when Chris discovers him peeing standing up. Although Daniel tries to reason with Lydia and Chris (Natalie is left out of the loop), they see it from a different angle. “You get to see your kids,” Lydia complains, “but we don’t get to see our dad. We just see a character.”

Act II also boasts some of the show’s best musical numbers. “Playing with Fire” has the chorus dressed as dancing Mrs. Doubtfires and “Let Go” spotlights Campbell’s (Miranda) enormous vocal talent. The spectacularly entertaining “He Lied to Me” features Kristin Angelina Henry, who milks every ounce out of her portrayal of a cuckolded flamenco dancer.

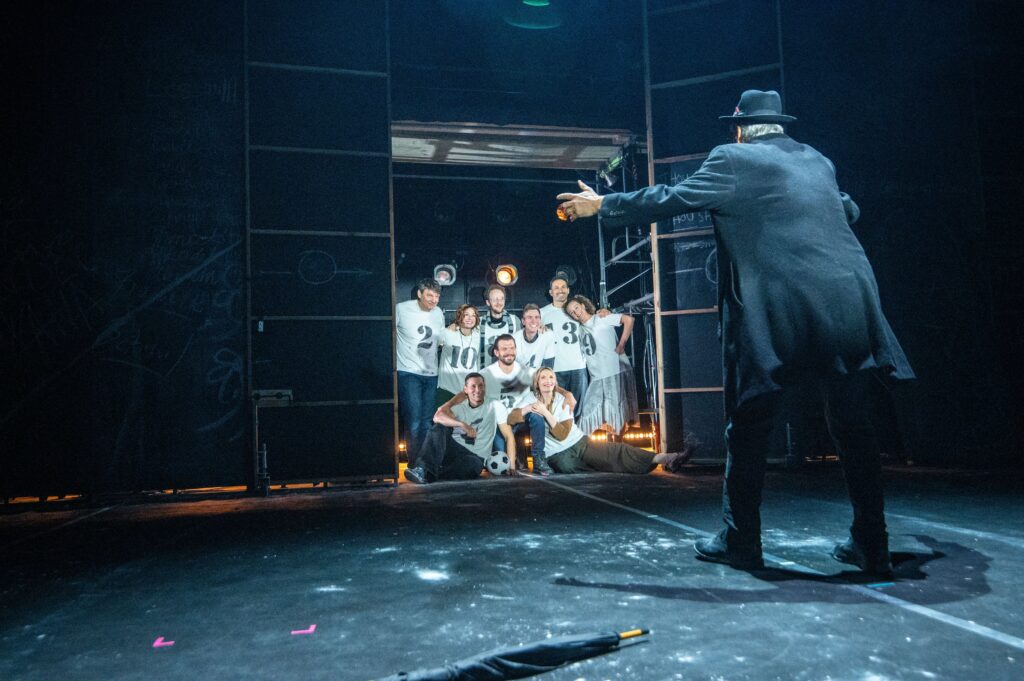

The mayhem culminates in a Marx-Brother scene when Daniel is scheduled to appear in the same restaurant as both Mrs. Doubtfire (Miranda’s birthday dinner) and himself (a job interview with Janet Lundy, television executive). He miraculously pulls off this scam thanks to bathroom help by Frank and André, but eventually the cat escapes its bag and everyone is in on the ruse.

The play concludes happily enough, but avoids tying too neat a bow. The best musical number of the show, “Just Pretend,” features Daniel (Smith) and Lydia (Sophia) in a dazzling duet that highlights Sophia’s singing chops. At the end of the day, the message is touching and real: “Even when you’ve lost your way,” Daniel sings to his daughter, “love will lead you home.”

‘Mrs. Doubtfire’ Music and Lyrics by Wayne and Karey Kirkpatrick. Book by Karey Kirkpatrick and John O’Farrell. Based on the Twentieth Century Studios Motion Picture. Arrangements and Orchestrations by Ethan Popp. Tour Direction by Steve Edlund. Tour Choreography by Michaeljon Slinger; Original Choreography by Lorin Latarro; Original Direction by Jerry Zaks. Scenic Design by David Korins; Costume Design by Catherine Zuber; Lighting Design by Philip S. Rosenberg; Sound Design by Keith Caggiano. Presented by Broadway in Boston and Work Lights Productions at the Emerson Colonial Theatre through Sept. 21.

For more information, visit https://boston.broadway.com/