By Shelley A. Sackett

Boston is a garden of many earthly delights, but none more eagerly awaited and appreciated than Commonwealth Shakespeare Company’s Free Shakespeare on the Common that, for 29 years, has invited people to lay down a blanket, bring a picnic dinner, and enjoy top-notch theater on Boston Common under a starry crescent-mooned sky.

Founding Artistic Director Steven Maler shares in the program notes that he chose As You Like It (which he also directs with surgical precision) because it is one of his favorite Shakespeare comedies. Based on the audience reaction last Wednesday, he may have added many new members to the play’s fan club.

Believed to have been written in 1599 and first published in 1623, As You Like It is the Bard at his most engaging — witty, silly and just plain fun. There is something to sate most palates, from political upheavals to love in various forms to a spritely forest bohemian refuge to mistaken identities and disguises. Yet, beneath the surface is a message that rings timely and (hopefully) true — even in the darkest times, the brightest light at the end of the tunnel is the flame of connection and resilience.

The play bears Shakespeare’s trademark of complex storylines, tangentially related characters, flowery language and one unparalleled speech (in this case, the one that begins, “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players…”)

Although billed as a comedy, the action opens on a dark note. Duke Frederick has banished his brother and rightful ruler, Duke Senior (both played by a plausible Maurice Emmanuel Parent), usurping a throne not rightfully his. Duke Senior has taken refuge in the Forest of Arden, and his daughter, Rosalind (a magnificent Nora Eschenheimer), has been allowed to remain in the court, mostly to keep her cousin, Celia (a charmingly bubbly Clara Hevia), company.

Enter into the court Orlando de Boys (Michael Underhill, an amalgam of James Dean, Marlon Brando and John Travolta). Orlando’s cruel older brother, Oliver (Joshua Olumide), has denied him the inheritance left to him by their recently deceased father. Looking for intervention from Duke Frederick, he instead literally steps into the court’s rink, forced to enter a wrestling match. He quickly dispatches the court champion, giving Orlando a chance to flash much muscle and toothiness. Rosalind, who witnesses the match, is thunderstruck with love at first sight.

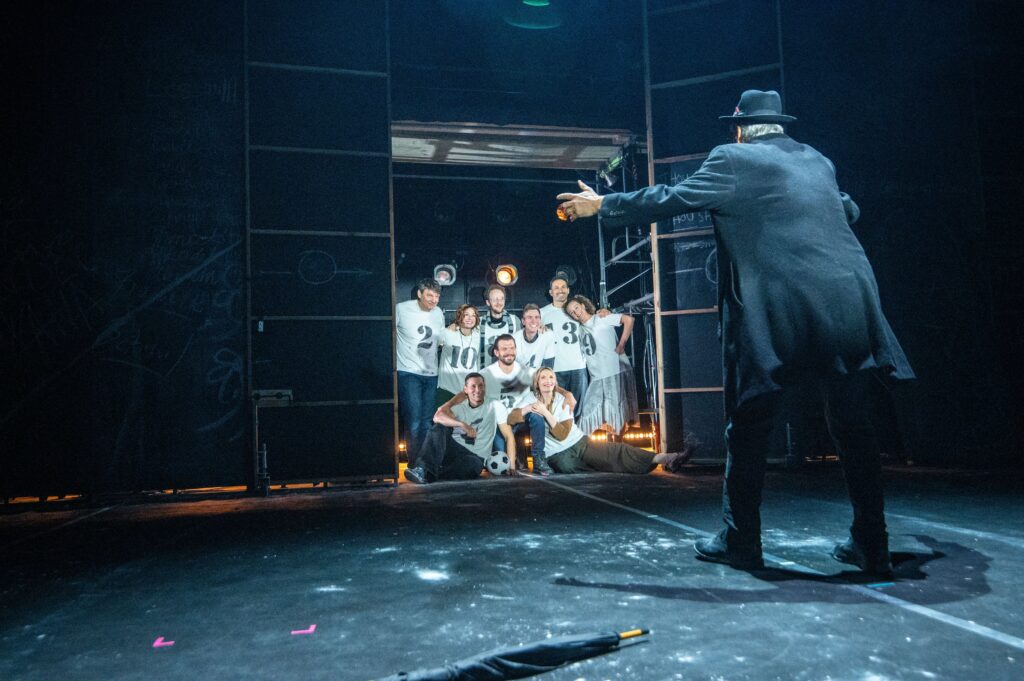

Director Maler struts his stuff early on with this scene. Riw Rakkulchon’s set of sometimes clumsy (for the actors) scaffolding and metal fences echoes the depravity of the evil duke and his lackies. (It also brings to mind front-page headlines of the horrors immigrant detainees encounter in 2025 detention camps.) Drum beats and metallic rhythms (sound by Aubrey Dube) heighten the scene’s tension and primal flavor.

But when Orlando and Rosalind lock eyes, time stands still, and we are suddenly transported by Shakespeare’s rom-com mastery.

The plot thickens when Orlando discovers Oliver is planning to kill him, fleeing to the Forest of Arden with his aged servant Adam (Brooks Reeves). Meanwhile, Frederick banishes Rosalind, accusing her of being a traitor. She and Celia decide to disguise themselves (Rosalind as a lad, Ganymede, and Celia as his sister, Aliena), take the droll and clownish Touchstone (a scene-stealing John Kuntz), and head — you guessed it — to the Forest of Arden.

The forest is a melting pot of characters. There is the banished duke and his band of loyal followers (Paul Michael Valley brings a gravitas and grace to his standout performance as the moody, contemplative Jacques and Remo Airaldi is a delight as Corin, bringing a Jonathan Winters-like humanity and accessibility to his role). They meet and interact with local farmers and town folk, including a shepherd (Cleveland Nicoll as the patient Silvius) in love with haughty shepherdess Phebe (Stephanie Burden, either miscast, misdirected, or both). And, of course, there is our newest band of merry refugees.

As stark and dark as the court set is with its chain link fence and threatening graffiti, the Forest of Arden is its opposite. Painted panels reminiscent of Henri Rousseau’s finest work brighten the stage, and musical interludes by Amiens (a terrific Jared Troilo) and guitarist Peter DiMaggio (who wrote the arrangements) add a light touch. The costumes (Miranda Giurleo) breathe a dream-like air into the scenes, but as we are constantly reminded, this exile is no dream.

The true stars and focus of the forest scenes, however, are Rosalind as Ganymede and Orlando. Orlando hangs love poems to Rosalind all over the forest and Rosalind (as Ganymede) befriends him, offering to let him practice on him/her so that when he finally meets Rosalind in the flesh, he will know how to woo her. The chemistry between the two is critical to keeping the ruse from becoming tedious, and Eschenheimer and Underhill have chemistry and talent to spare. Eschenheimer in particular is a spritely delight as she pretends to be a man pretending to be a woman.

Other standouts include Valley, who brings a particular poignance and freshness to the familiar “All the world’s a stage…” speech, and Kuntz, as the harlequin-clad Touchstone.

After a number of plot twists and turns (including a lion attack, sibling reconciliation, and love connections and triangles), all ends well with marriages, revealed identities and renounced usurpations. Maler’s thoughtful, playful direction, a stellar cast, and a fun yet thought-provoking script make for yet another fabulous summer production from the beloved and reliable Commonwealth Shakespeare Company.

‘As You Like It’ — Written by William Shakespeare. Directed by Steven Maler. Scenic Design by Riw Rakkulchon; Costume Design by Miranda Giurleo; Lighting Design by Eric Southern; Sound Design by Aubrey Dube. Presented by Commonwealth Shakespeare Production on Boston Common through August 10.For more information, visit https://commshakes.org/production/asyoulikeit25/