Martha Graham Dance Company’ — Presented by Celebrity Series of Boston at Emerson Cutler Majestic. Run has ended.

By Shelley A. Sackett

The last time I saw a Martha Graham piece performed was at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in October 2023, when I had the random good fortune to attend its exhibition, Art for the Millions: American Culture and Politics in the 1930s. As part of that exhibit, dancers from the Martha Graham Dance Company staged some of Graham’s most powerful ’30s solos in galleries throughout the museum.

I was lucky enough to catch “Lamentations” in the New Greek and Roman Galleries, the spectacular “museum-within-the-museum” built to display the Met’s extraordinary collection of Hellenistic, Etruscan, South Italian, and Roman sculpture.

Graham’s 1930 work, set to Hungarian Zoltàn Kodàly’s plaintive music, features a single dancer whose angular moves inside a stretchy fabric cocoon have long marked Graham’s trailblazing style. Over a mere four minutes, the dancer fights what feels like an eternal battle to get out of her encasement. Only her face, hands and feet are visible, yet the geometric shapes she creates epitomize her fruitless struggle. She pleads and prays, but there is no escape. Graham called the piece “the personification of grief.”

Seeing the timeless, sculptural piece in a sun-filled atrium with an audience of ancient statues was nothing short of sublime.

Its recent performance at the 1,200-seat beaux-art Emerson Cutler Majestic, though a less intimate setting, was no less astonishing.

Few dance companies have transfigured the art of contemporary dance quite like Martha Graham’s. Since the company’s founding in 1926, Graham’s signature style has remained a bedrock of American modern dance and continues to be taught worldwide.

In anticipation of the company’s 100th birthday celebration in 2026 (GRAHAM100), the Boston Celebrity Series brought the legendary troupe to Boston for three special appearances to kick off its own 2024/2025 Season Dance Series.

The Friday night capacity show illustrated why Graham remains the gold standard of contemporary dance choreography.

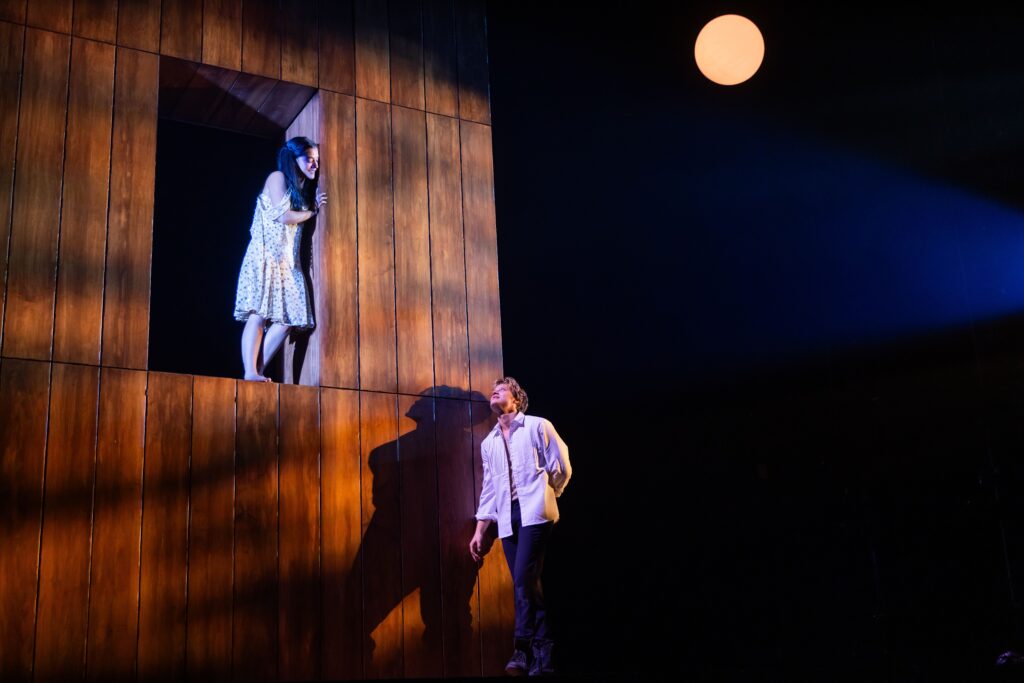

The program opened with “Dark Meadow Suite (1946), highlights from her longer “Dark Meadow.” The full ensemble (featuring Lloyd Knight and Anne Souder) performs an ancient mating ritual as part of Graham’s American homage to a mythological rite of spring.

The piece opens with a Greek chorus of five women who circle trancelike, stamping a primordial rhythm with their bare feet. Thick, rich music by Carlos Chávez sets the auditory stage for stunning, sensual, animal-like movements as dancers join, separate, and pulsate in perfect synchronicity. Playful lighting (Nick Hung) adds color and texture and black and orange flowing costumes (Martha Graham) are equal parts elegance and flirty frolic. Knight and Souder are the embodiment of grace as they perform their coupling ceremony, which Graham described as “a re-enactment of the mysteries which attend the eternal adventure of seeking.”

Close Graham friend and collaborator Agnes de Mille, the storyteller niece of filmmaker Cecil B. DeMille, choreographed the iconic “Rodeo or The Courting at Burnt Ranch.” For its GRAHAM100 3-year celebration, Gabriel Witcher rearranged Aaron Copeland’s trademark music for a six-piece bluegrass ensemble. Celebrating the diverse genesis of America, the piece is a series of humorous vignettes featuring dancers clad in full-blown cowpoke, cowgirl, and genteel pioneer women’s regalia.

Like a silent movie, the action takes place on a Saturday afternoon and evening on a ranch in the southwest. DeMille referred to her work as “a pastorale, a lyric joke,” and as The Cowgirl, Laurel Dalley Smith manages to be sassy and funny while displaying serious dancing talent. The piece flits from a Wyatt Earp TV set to a mariachi band to a barn dance, loving spoofs that straddle Broadway blockbuster musicals, classical ballet, and cowboy rodeo activities. In between are tastes of square dances, polkas, and couples pairing and unpairing. Screen projections that change from ranch to sunset to starry night to barn dance are effective without being hokey.

Post intermission, the afore-described “Lamentations” is even more stunning on the heels of the slapstick-like “Rodeo.” So Young An, the recipient of the International Arts Award and the Grand Prize at the Korea National Ballet Grand Prix, is a talent to be reckoned with.

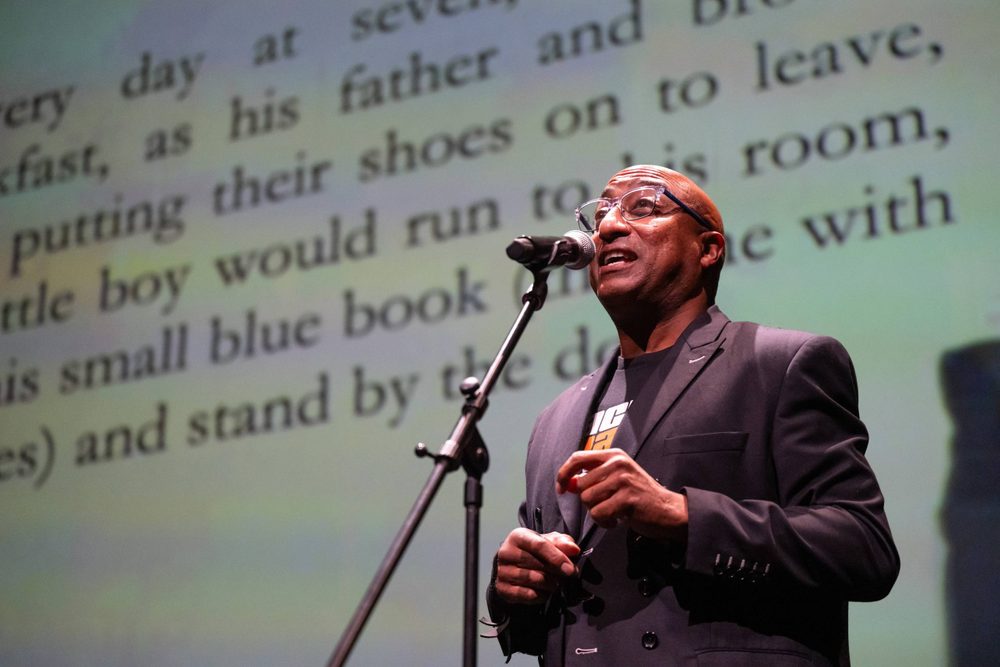

The evening ends with the 2024 piece, “The People.” Choreographed by Jamar Roberts, who describes his work as “part protest, part lament,” the piece resonates with references to American history. Dancers are both uplifting paeans to the hope and promise of American folk music and downtrodden, burdened examples of what can happen when America doesn’t live up to its promises. A new score by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer and American roots musician Rhiannon Giddens (arranged by Witcher) spotlights rich, throaty harmonies peppered with pockets of poignant silence.

The last time the Martha Graham Dance Company adorned Boston’s stage was in 2005. Judging from the exuberant standing ovation its 2024 audience bestowed last Friday evening, one can only hope they got the message that they have been away far too long.